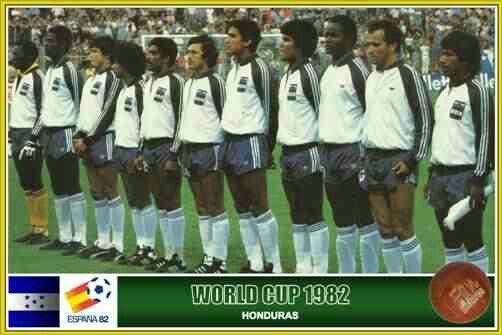

A nation that arrived early

Honduras qualified for its first World Cup in 1982, ahead of many neighbours with stronger reputations. The tournament in Spain is often remembered for results rather than performances, but Honduras were competitive. They drew 1–1 with Spain, held Northern Ireland, and lost narrowly to Yugoslavia. Players like Gilberto Yearwood, Antonio La Volpe’s contemporary Ramón Maradiaga, and goalkeeper Julio César Arzú gave the team credibility. Yet that early arrival created an expectation Honduras would struggle to meet for decades.

Domestic football without insulation

After 1982, Honduran football lacked the institutional protection needed to convert exposure into continuity. The Liga Nacional de Honduras produced competitive clubs such as Olimpia, Motagua, Real España, and Marathón, but financial margins were thin. Players left early for Costa Rica, Mexico, or the United States. Clubs rarely retained squads long enough to mature together. Unlike Mexico’s Primera División or Costa Rica’s increasingly professionalised system, Honduras remained vulnerable to disruption.

Regional competition as reality check

Between World Cups, Honduras measured itself through CONCACAF rather than FIFA tournaments. The CONCACAF Championship, later the Gold Cup, became both opportunity and limitation. Honduras won the 1981 championship, but subsequent editions exposed inconsistency. Strong runs were followed by early exits. Matches against Costa Rica, Mexico, and the United States defined progress more than global ambitions. Honduras were competitive, rarely dominant.

The club game as national substitute

With World Cups absent, domestic clubs carried international identity. Olimpia’s runs in the CONCACAF Champions’ Cup in the late 1980s and 1990s mattered deeply. Matches against Cruz Azul, América, and Saprissa were treated as proxies for international validation. Stadiums like Estadio Nacional Tiburcio Carías Andino became places where continental relevance felt possible, even if national qualification remained elusive.

Lost cycles and short memories

The 1990s were marked by near-misses. Honduras reached the final round of CONCACAF qualification for France 1998 but fell short behind Mexico and the United States. Players such as Carlos Pavón, Amado Guevara, and Milton Núñez represented a generation good enough to compete regionally but inconsistent over long qualifying cycles. Coaching changes were frequent. Long-term planning was rare.

The diaspora effect

Unlike some Central American nations, Honduras did not benefit early from a strong European or North American diaspora pipeline. Players moved abroad, but usually late and to mid-level leagues. Pavón found success in Italy with Udinese and Napoli. David Suazo’s later move to Cagliari and Inter would come after qualification was finally achieved again. Between World Cups, Honduras produced individuals rather than systems.

Political instability and football drift

Domestic instability affected football governance. Federation leadership changed often. Youth development programmes were inconsistent. Investment flowed unevenly. While football remained culturally important, it lacked political protection. This contrasted with Mexico’s centralised control or the United States’ long-term structural planning. Honduras existed in between: passionate, talented, but exposed.

The Gold Cup paradox

Honduras often performed better in tournament football than in qualifiers. Third-place finishes in the Gold Cup showed they could compete when momentum mattered. Yet World Cup qualification demanded consistency across hostile away matches in San José, Mexico City, and Columbus. Honduras struggled with depth, not belief. The gap was logistical and structural, not emotional.

Support without reward

Supporter culture did not fade between World Cups. Matches against El Salvador and Costa Rica still carried historic weight. Club rivalries between Olimpia and Motagua remained intense. Football mattered regardless of qualification. This sustained relevance masked the frustration of absence. Honduras were never forgotten by their supporters, even when FIFA forgot them.

Breaking the cycle

When Honduras finally returned to the World Cup in 2010, it felt less like a breakthrough than an overdue correction. The intervening decades had not been empty; they were formative. Players like Guevara, Pavón, and Suazo bridged eras. Clubs learned to survive without stability. The federation learned, slowly, that endurance alone was not enough.

What the gap reveals

Honduras between World Cups is not a story of failure. It is a story of a football nation living permanently in qualification mode, defined by proximity rather than presence. The absence shaped identity. It sharpened rivalries. It forced reliance on clubs and regional tournaments. When Honduras returned to the global stage, they did so carrying decades of unfulfilled expectation.

Between World Cups, Honduran football learned how to wait without disappearing.