A town built before football

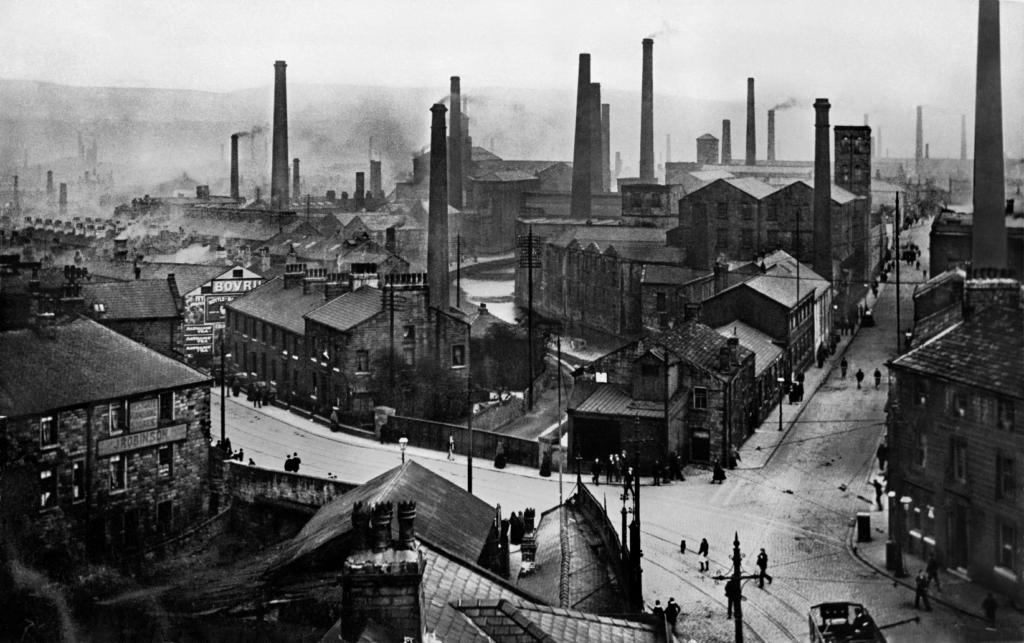

Long before Burnley became a football reference point, it was an industrial one. The town’s identity was forged in cotton mills, coal yards, and engineering works that shaped not only its economy but its rhythms of life. Shift patterns dictated leisure time, Saturdays were communal release valves, and football became less an escape than an extension of working life. When Burnley Football Club emerged in the late 19th century, it did not create a culture so much as inherit one.

That inheritance would shape the club for more than a century, long after most top-flight teams had shed their industrial roots.

Turf Moor as an industrial space

Turf Moor was never a destination stadium in the modern sense. It was embedded in the town, surrounded by terraced housing and industrial infrastructure. Supporters walked to matches along the same routes they used for work. There was no separation between labour and leisure, no rebranding of football as entertainment detached from place.

The stadium reflected that reality. It was functional, unpretentious, and resistant to cosmetic change. Even as English football modernised, Turf Moor retained the feel of a workplace gathering point rather than a leisure complex.

Football as collective labour

Burnley’s football culture mirrored industrial values. The team was expected to work, not perform. Effort was not a virtue; it was a baseline requirement. Players who failed to show commitment were rejected regardless of talent.

This attitude was not performative toughness. It was cultural continuity. In a town where manual labour defined status, footballers were expected to respect that context. Burnley players were not elevated above supporters; they were viewed as representatives of them.

The club that never chased glamour

While other clubs pursued expansion, relocation, and rebranding, Burnley remained static. This was not stubbornness for its own sake. It reflected an industrial mindset that valued stability over growth, reliability over ambition.

Financial conservatism became part of the club’s identity. Wages were controlled, signings were cautious, and risk was avoided wherever possible. This approach kept Burnley solvent when others collapsed, but it also limited their appeal in a changing football landscape.

Success without transformation

Burnley’s greatest footballing successes did not alter the club’s self-image. League titles and European qualification were absorbed rather than celebrated. There was no attempt to reposition Burnley as a national or international brand.

In an industrial culture, success was something you earned and then returned to work. Burnley embodied that philosophy. Triumph did not justify excess.

The slow erosion of industry

As mills closed and industries declined, Burnley faced the same structural challenges as many northern towns. Unemployment rose, populations shifted, and community cohesion weakened. Football clubs elsewhere used modernisation to detach themselves from local decline.

Burnley did not. The club remained tied to the town’s fortunes, for better or worse. As industrial identity eroded, Burnley became one of its last visible symbols.

Supporters as custodians

Burnley’s supporters did not consume football; they safeguarded it. Attendance was seen as responsibility rather than choice. Loyalty was inherited, not marketed.

This created a fan culture resistant to change. New ownership models, global outreach, and aesthetic rebranding were met with suspicion. Burnley supporters valued continuity over innovation, even when innovation might have offered short-term gains.

The Premier League anomaly

Burnley’s return to the Premier League in the 21st century felt anachronistic. A club defined by industrial values operating within a global entertainment product created friction.

Yet Burnley did not adapt its identity to fit the league. Instead, it forced the league to accommodate it. Tactical pragmatism, financial restraint, and cultural insularity became survival tools.

The club’s presence in the Premier League was not aspirational. It was defiant.

Industrial discipline on the pitch

Burnley’s football reflected the discipline of industrial labour. Roles were clearly defined. Individual expression was secondary to collective structure. Systems mattered more than stars.

This approach was often dismissed as outdated, but it was deeply coherent. It mirrored the town’s historical organisation of work: everyone knew their task, and deviation was discouraged.

Why Burnley outlasted others

Many clubs with similar origins attempted to reinvent themselves and failed. Burnley survived by refusing reinvention. The club’s industrial identity became a stabilising force in an unstable football economy.

This survival came at a cost. Burnley rarely attracted neutrals. They were unfashionable by design. But they endured.

A town reflected in a team

Burnley Football Club did not represent an industrial past; it extended it. As factories disappeared, the club carried forward values that had lost their physical context.

In this sense, Burnley became more than a football club. It became a cultural archive, preserving attitudes and behaviours that no longer dominated daily life.

Modern football, old foundations

Today, Burnley operate in a sport defined by capital, visibility, and global reach. Yet beneath modern structures, the club’s core remains industrial. Decisions are cautious. Identity is protected. Change is managed reluctantly.

This makes Burnley an anomaly, but also a reminder.

Why this identity matters

Burnley’s story challenges the idea that football progress requires cultural erasure. The club demonstrates that identity rooted in place can survive modern pressures, even if it never thrives in conventional terms.

In an era of franchises and floating loyalties, Burnley stand as one of the last examples of football as civic expression rather than product.

The last of its kind

Burnley are not the only club born from industry, but they may be the last to still live by it. Their football culture was shaped by mills and mines, not marketing plans.

That culture has outlasted the industries that created it.

And in doing so, Burnley have become something rare in modern football: a club whose identity is not remembered, but still lived.