Arrival without a script

Uganda arrived in Ghana for the 1978 Africa Cup of Nations without the weight usually carried by finalists. They were not continental heavyweights, nor were they framed as a romantic outsider in the international press. Yet within East Africa, qualification itself had already been read as a quiet statement. The Cranes were competitive, disciplined, and hardened by regional football, even if few imagined how far they would go.

AFCON 1978 would become the defining tournament in Uganda’s football history. Not because of a trophy, but because it briefly placed the country at the centre of African football — and revealed both the possibilities and limits of the game under extraordinary political pressure.

The road to Ghana

Uganda’s qualification reflected their status within East and Central African football. The Cranes were regular contenders in CECAFA competitions, where familiarity bred resilience. Matches were often physical, tactically conservative, and shaped by difficult pitches. Uganda learned to manage games rather than overwhelm opponents.

The national team drew heavily from domestic clubs such as SC Villa and Express, whose players were accustomed to hostile environments and high-stakes regional fixtures. What Uganda lacked was sustained exposure beyond their immediate football neighbourhood. AFCON offered not only competition, but confrontation with unfamiliar styles and expectations.

Football and the state

By 1978, Uganda existed under the rule of Idi Amin. Sport, like nearly everything else, operated within a political frame. Football was encouraged as a symbol of strength and unity, but it was also monitored. Success brought praise and proximity to power. Failure carried uncertainty.

For players, the stakes were never purely sporting. Representing the national team meant representing the state itself. This reality did not always manifest as direct interference, but it shaped the atmosphere around the squad. Discipline was prized. Public embarrassment was not tolerated. The pressure travelled with the team to Ghana.

A group that opened doors

Uganda’s group-stage performances defied expectations. Rather than being overwhelmed, the Cranes proved organised and efficient. Their defensive shape frustrated opponents, while moments of attacking directness produced results. Matches were won not through dominance, but through control of tempo and territory.

Each result recalibrated how Uganda were viewed. What began as surprise quickly became curiosity. Opponents struggled to break down a team comfortable without possession and unafraid of physical confrontation. Uganda advanced not by reinventing themselves, but by trusting what they already knew.

Momentum and belief

As the tournament progressed, belief grew internally. The players sensed opportunity, even if few articulated it openly. Knockout football rewarded discipline, and Uganda’s approach suited the format. They absorbed pressure, exploited mistakes, and defended leads with determination rather than panic.

For supporters back home, following events through radio reports and delayed newspaper coverage, the sense of disbelief deepened. Uganda were not merely participating; they were competing with authority. Each round rewritten expectations that had stood for decades.

Reaching the final

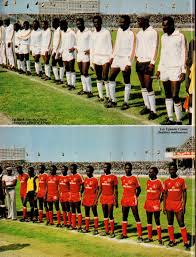

Uganda’s path to the final was unprecedented. No East African nation had reached this stage of the Africa Cup of Nations before. The achievement alone altered Uganda’s footballing self-image. Suddenly, the Cranes were no longer peripheral participants. They were contenders.

The final, against hosts Ghana, carried symbolic weight. Ghana represented continental pedigree, infrastructure, and experience. Uganda represented discipline, regional pride, and improvisation. The contrast was stark, but the gap felt bridgeable — at least for ninety minutes.

The final and its limits

The final itself exposed the limits of Uganda’s remarkable run. Ghana’s depth, composure, and attacking variety proved decisive. Uganda fought, but fatigue and pressure accumulated. Defensive solidity cracked under sustained assault, and the scoreline reflected the difference in experience.

Yet the defeat did not erase what came before. Uganda had reached the summit of African football under circumstances few could have predicted. Losing the final was painful, but it did not diminish the magnitude of the journey.

Return without celebration

Despite finishing as runners-up, Uganda’s return home was subdued. The political climate discouraged spontaneous celebration. Public narratives were carefully managed. The achievement was acknowledged, but not mythologised. Football success did not exist independently of state control.

For the players, recognition was uneven. There were no sustained pathways to professional careers abroad, no structural reforms that immediately followed. The moment passed without being fully harnessed.

Memory and erosion

Over time, AFCON 1978 became a strangely fragile memory. It was referenced, but rarely explored in depth. Later generations knew Uganda had once reached an AFCON final, but the details blurred. Names faded. Matches collapsed into a single line of history.

Part of this erosion reflected Uganda’s long absence from subsequent tournaments. Without regular continental presence, the 1978 achievement stood isolated, difficult to contextualise within a continuous footballing story.

What 1978 revealed

AFCON 1978 revealed what Ugandan football could achieve under extreme pressure and limited resources. It also revealed what it lacked: continuity, infrastructure, and insulation from political volatility. The success was real, but it was not sustainable in its existing form.

Rather than launching an era, the tournament became a peak surrounded by long valleys. Uganda would not return to an AFCON final. For decades, they would struggle to return at all.

A moment that still matters

Uganda’s 1978 Africa Cup of Nations campaign remains one of African football’s most improbable runs. It was not built on star power or tactical innovation, but on cohesion, discipline, and circumstance.

In the end, AFCON 1978 stands as both achievement and warning. It showed how far Ugandan football could rise — and how quickly momentum could dissipate when systems failed to follow success. The final was lost, but the moment endures, waiting to be fully remembered.