Prosperity without foundations

The 1920s are often framed as football’s moment of consolidation: leagues formalised, crowds expanded, and the sport rooted itself into national cultures. Yet the decade also produced a trail of collapsed clubs, many of them founded during moments of optimism and erased before stability arrived.

These clubs did not fail in decline. They failed during growth.

Post-war enthusiasm and rapid formation

In countries rebuilding after the First World War, football became a civic outlet. In Germany, dozens of new Verein sides emerged during the early Weimar years. In Austria and Czechoslovakia, urban districts formed clubs tied to neighbourhood identity rather than long-term planning.

Vienna alone saw multiple short-lived teams enter and exit regional leagues during the early 1920s, unable to keep pace with the professionalising elite like Rapid Wien or First Vienna FC. Similar patterns appeared in northern Italy, where factory-backed teams briefly surfaced in Lombardy and Piedmont, only to vanish within a few seasons.

The boom encouraged creation. It did not ensure survival.

England’s forgotten professional experiments

Even in England, where league football was already established, the 1920s produced casualties. Clubs admitted to the expanded Football League Third Division struggled to cope with travel costs and falling local interest.

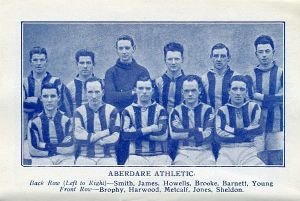

Aberdare Athletic, elected to the Football League in 1921, survived barely six seasons before being voted out in 1927. Despite respectable crowds in South Wales, gate receipts could not offset travel expenses or competitive imbalance. Their removal is often treated as administrative routine, but it reflected a deeper instability: expansion had outpaced sustainability.

Other clubs, such as Durham City, followed similar paths. Professional status arrived before infrastructure.

Central Europe and the cost of professionalism

In Central Europe, the problem was sharper. Austria introduced professionalism officially in 1924, transforming the Wiener Liga almost overnight. Established clubs adapted. Newer ones did not.

Clubs like SC Rudolfshügel, once competitive in Vienna’s early championships, collapsed financially under the weight of player wages and ground requirements. Others merged or disappeared entirely, leaving little trace beyond league tables.

In Hungary, smaller Budapest sides folded as MTK and Ferencváros consolidated dominance. Professionalism did not just elevate the elite; it accelerated the removal of the fragile.

France’s unstable pre-professional era

France in the 1920s presented a different model: officially amateur, privately strained. Clubs competed in regional leagues under the USFSA and later FFFA structures, but payments existed beneath the surface.

Paris alone hosted dozens of competitive sides, many tied to workplaces or local associations. Clubs such as CA Paris survived, but many rivals dissolved quietly as costs rose without professional safeguards. Without a national league until the 1930s, instability went largely undocumented.

The boom created ambition without clarity.

South America’s uneven growth

In South America, the 1920s are remembered for Uruguay’s Olympic triumphs and Argentina’s growing crowds. Yet outside the dominant centres, instability persisted.

In Montevideo, clubs beyond the Primera División elite struggled to remain solvent as attendances concentrated around Nacional and Peñarol. Smaller sides entered and exited the league structure rapidly, particularly during disputes between amateur and professional factions later in the decade.

In Argentina, the split between amateur and professional leagues at the end of the 1920s exposed years of financial imbalance. Several clubs that had expanded aggressively earlier in the decade failed to survive the transition.

Leagues that expanded too fast

Across Europe, league expansion was both opportunity and trap. Germany’s regional leagues grew in scale, demanding longer travel and more fixtures. Italy’s Prima Division expanded before its reorganisation into Serie A, leaving smaller provincial clubs overstretched.

Promotion often proved fatal. Clubs built to dominate local competition found themselves outmatched economically and competitively at higher levels. Relegation did not always follow; withdrawal did.

The league system assumed resilience that many clubs did not possess.

Civic pride with short memory

Many boom-era clubs were tied closely to municipal enthusiasm. Local councils supported ground construction. Newspapers celebrated new colours and crests. Yet support was informal and reversible.

When local economies tightened or political priorities shifted, backing disappeared. Clubs without private capital or historical prestige collapsed quickly. Their stories rarely extended beyond a handful of seasons.

Football history tends to remember institutions that endured. The 1920s produced many that did not.

Why collapse followed growth

The boom punished clubs that mistook visibility for security. Rising crowds created obligations: better grounds, paid players, longer seasons. For clubs without administrative experience, growth accelerated failure.

Those that survived learned restraint. Those that folded absorbed the consequences of expansion and quietly shaped reform through their absence.

What remains

By the end of the decade, football looked more stable than it had in 1919. That stability was built partly on disappearance. Clubs that folded with the boom were not anomalies; they were casualties of transformation.

Their names are missing from modern narratives, but their failures explain why others learned to endure.