Survival was not guaranteed

Football’s endurance often feels inevitable in hindsight, but survival was the product of pressure, compromise, and constant adaptation. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, football was not stronger than rival sports. It was simply more flexible. Where others clung to tradition, football learned to bend without breaking, absorbing change while preserving its core appeal.

The game survived not because it was stable, but because instability forced evolution.

Simplicity at its core

At its heart, football required very little. A ball, open space, and agreement on basic rules were enough to begin. This simplicity allowed football to spread faster than sports that depended on specialist equipment, facilities, or formal membership.

Cricket needed pitches, gear, and long stretches of time. Rugby demanded physical commitment not everyone could give. Football could be played anywhere, briefly or endlessly, formally or informally. That accessibility ensured it never relied on a single social group for survival.

Even when clubs collapsed, the game itself remained.

Local ownership of the game

Football survived because it belonged to communities rather than institutions. In the absence of strong governing bodies, towns, schools, and workplaces shaped the game to their own needs.

This local ownership created emotional investment. Clubs represented neighbourhoods, trades, or shared identities. Matches mattered not because of trophies, but because they reflected pride and belonging.

When football struggled structurally, it thrived socially. That distinction proved decisive.

The willingness to argue and reform

Few sports survived as many internal conflicts as football. Disputes over rules, violence, professionalism, and class nearly fractured the game repeatedly. Yet football’s leaders showed an unusual willingness to debate and revise.

Instead of enforcing rigid tradition, football evolved through compromise. Hacking was restricted. Handling clarified. Offside refined. Matches shortened. Rules were rewritten not once, but continuously.

Survival depended on accepting imperfection and improving through disagreement.

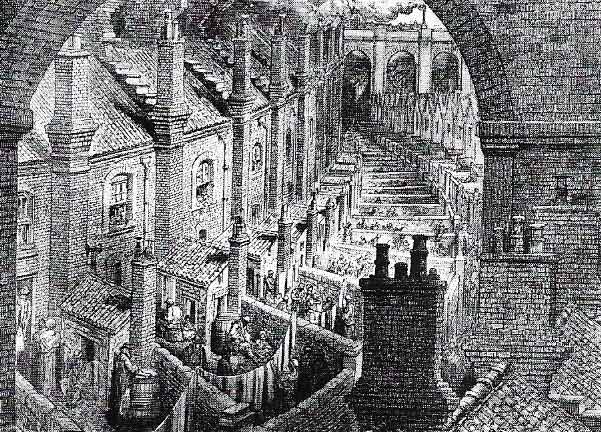

Urbanisation and timing

Football emerged at the perfect historical moment. Industrialisation created dense urban populations with limited leisure time and a need for collective release. Football’s short matches and seasonal flexibility suited this new reality.

Railways allowed teams to travel. Newspapers created narratives around clubs. Towns sought symbols of identity in an era of rapid change.

Football did not resist modernity. It aligned with it.

Spectatorship before spectacle

Early football survived because it welcomed spectators before it learned how to monetise them. Crowds gathered organically, without tickets, seating, or segregation. Watching football was informal and participatory.

Spectators felt involved rather than excluded. They argued, advised, celebrated, and criticised openly. This intimacy created loyalty long before stadiums or professional leagues formalised support.

Football became a habit before it became a product.

The acceptance of professionalism

One of the most critical reasons football survived was its eventual acceptance of professionalism. Resistance delayed it, but acceptance saved it.

Paying players allowed working-class participation on equal terms. It stabilised clubs, improved quality, and created continuity. Football stopped relying on spare time and began rewarding commitment.

Where other sports resisted change and narrowed their base, football widened it.

Competitive balance and uncertainty

Football also survived because it embraced uncertainty. Unlike sports dominated by fixed hierarchies, football allowed rapid change. New clubs could rise. Old powers could fall.

Results remained unpredictable enough to sustain interest. Success was not monopolised permanently, especially in football’s early decades. That sense of possibility kept people engaged even when structures were weak.

Uncertainty was not a flaw. It was fuel.

Emotional intensity

Football condensed emotion into short, repeatable moments. Goals were rare enough to matter, but common enough to sustain hope. Matches could swing suddenly, rewarding belief until the final moment.

This emotional rhythm proved addictive. Football offered drama without requiring deep understanding. Anyone could feel it immediately.

Other sports explained themselves. Football announced itself.

Adaptation across borders

As football spread beyond England, it adapted again. Different cultures reshaped it without abandoning its essence. Styles varied, rules flexed slightly, and identities multiplied.

Instead of fragmenting, football absorbed these differences. International competition later reinforced unity rather than division.

A game that could belong everywhere could not easily disappear anywhere.

Survival through imperfection

Football survived because it never waited to be perfect. It accepted poor pitches, bad referees, unfair systems, and flawed governance as temporary realities rather than fatal problems.

Each generation believed the game was broken. Each generation fixed enough to continue.

That tolerance for imperfection, more than any rule or institution, ensured survival.

Why survival still matters

Understanding why football survived helps explain why it remains vulnerable. Its strength has always come from adaptability, accessibility, and shared ownership.

When football drifts too far from those roots, it risks forgetting how fragile its beginnings were.

Football survived once by changing. It will survive again only by remembering why.