A moment before the outward pull

In the early 1980s, Nigerian football briefly reached a point where staying home still meant relevance. Domestic clubs mattered. The local league commanded attention. Players became national figures without first needing European validation. It was a narrow window, but one in which Nigerian football felt complete within its own borders.

This period did not last long. Within a decade, the centre of gravity would shift decisively abroad. But for a few seasons, Nigeria’s domestic game stood at its strongest.

A league with real weight

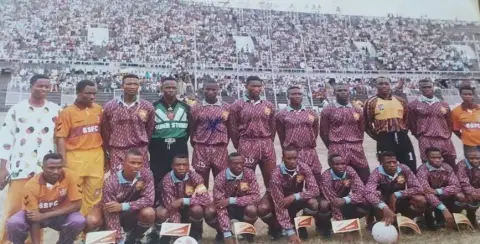

The Nigerian league of the late 1970s and early 1980s was competitive, physical, and widely followed. Clubs such as Shooting Stars, Stationery Stores, Bendel Insurance, Rangers International, and Raccah Rovers drew large crowds and genuine regional loyalty.

Matches were events. Not just local fixtures, but national talking points. Results travelled by radio, newspapers, and word of mouth. Players were recognised faces in their cities, and club identities were deeply tied to place and community.

Unlike later decades, the league did not feel like a waiting room for Europe. It was the destination.

Continental relevance without departure

Nigerian clubs were not only strong domestically but competitive across Africa. Shooting Stars reached the African Cup Winners’ Cup final in 1976 and the African Cup of Champions Clubs final in 1984. Rangers International were continental regulars, feared for their intensity and organisation.

These performances mattered because they were achieved with home-based squads. Nigerian teams were not seen as talent exporters but as rivals in their own right. Travelling to Nigeria was difficult for visiting teams, not just because of conditions, but because of quality.

Domestic success translated into continental respect.

The Super Eagles were mostly local

The national team reflected the strength of the domestic game. Many Super Eagles players of the early 1980s were league-based. They trained together regularly, understood each other’s games, and arrived in camp with shared tactical habits.

Nigeria’s victory at the 1980 Africa Cup of Nations, hosted in Lagos, was built largely on domestic players. That triumph reinforced the belief that Nigerian football did not need external validation to succeed.

The national team and the league felt connected rather than separate.

Stadiums as social centres

Stadiums like the National Stadium in Surulere, Liberty Stadium in Ibadan, and Nnamdi Azikiwe Stadium in Enugu were central to football culture. These were not just venues but gathering points, places where football intersected with politics, music, and identity.

Crowds were close, vocal, and demanding. Players felt pressure but also protection. Home advantage was real, shaped by atmosphere rather than intimidation alone.

Football was woven into public life, not isolated as entertainment.

Economic balance before the break

This era coincided with a fragile but functional economic balance. While Nigeria faced broader challenges, clubs could still offer players stability, status, and modest financial security.

Europe was not yet an automatic upgrade. Transfers were rare, uncertain, and often risky. Staying home did not mean obscurity. It meant visibility, pride, and continuity.

Once that balance shifted, the domestic peak began to erode.

Coaching continuity and local knowledge

Coaching during this period relied heavily on local expertise. Trainers understood conditions, player psychology, and regional differences. Tactical approaches were pragmatic, shaped by travel demands, pitch quality, and climate.

There was less obsession with imported systems and more emphasis on managing reality. Matches were won through fitness, organisation, and collective effort rather than individual stardom.

That grounding gave Nigerian football an identity rooted in circumstance.

Media attention without overload

Coverage was limited but focused. Newspapers followed clubs consistently, radio commentary reached far beyond stadiums, and football debates filled public spaces.

Without saturation, interest deepened rather than diluted. Fans followed teams over seasons, not highlights over minutes. Football culture grew through repetition and shared memory.

This slower pace helped sustain loyalty.

The beginning of the outward drain

By the mid-1980s, cracks appeared. European clubs began recruiting more aggressively. Agents spotted opportunities. The promise of financial security abroad grew harder to resist.

As players left earlier and more frequently, the league lost continuity. Clubs struggled to rebuild year after year. The sense of permanence that defined the early 1980s faded.

The domestic peak had passed.

Why the moment still matters

The early 1980s stand as proof that Nigerian football once thrived internally. It challenges the idea that success must always be external. This was a period when clubs mattered, crowds believed, and players became legends without leaving home.

That moment did not fail because of lack of talent. It ended because structures could not protect it.

Understanding this era is not nostalgia. It is context. Nigerian football’s future debates make little sense without remembering when its domestic game once stood tall.