From novelty to national ritual

Knockout competitions existed before the 1920s, but they were often secondary to leagues, irregular in prestige, and uneven in organisation. The decade changed that balance. National cups stopped being experimental additions and became cultural events, capable of uniting regions, classes, and football cultures within a single narrative.

What mattered was not just who won, but that everyone cared.

England and the weight of the FA Cup

The FA Cup predated the 1920s by decades, yet its cultural dominance matured in the interwar years. By the early 1920s, the Cup had become a national ritual, followed across divisions and regions.

Finals at Wembley Stadium, opened in 1923, transformed the competition’s meaning. The so-called White Horse Final between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United drew unprecedented attention, not because of the match itself, but because it symbolised football’s reach.

Cup runs by smaller clubs mattered deeply. Cardiff City’s path to the 1927 final, and eventual victory over Arsenal, resonated beyond Wales. The Cup allowed peripheral clubs to briefly occupy the national stage.

It was no longer just a tournament. It was shared experience.

France and the Coupe de France

In France, the Coupe de France became the country’s most unifying football institution. Founded during the First World War, it flourished in the 1920s because it ignored regional hierarchies.

Amateur and professional clubs competed together. Teams from industrial north, Mediterranean south, and colonial territories entered the same draw. Travel was difficult, but the idea was powerful.

Clubs such as Red Star and CA Paris became early cup symbols, while smaller provincial teams gained visibility through unlikely runs. The Coupe de France mattered because it told stories France’s fragmented league system could not.

It created a national football conversation before a national league existed.

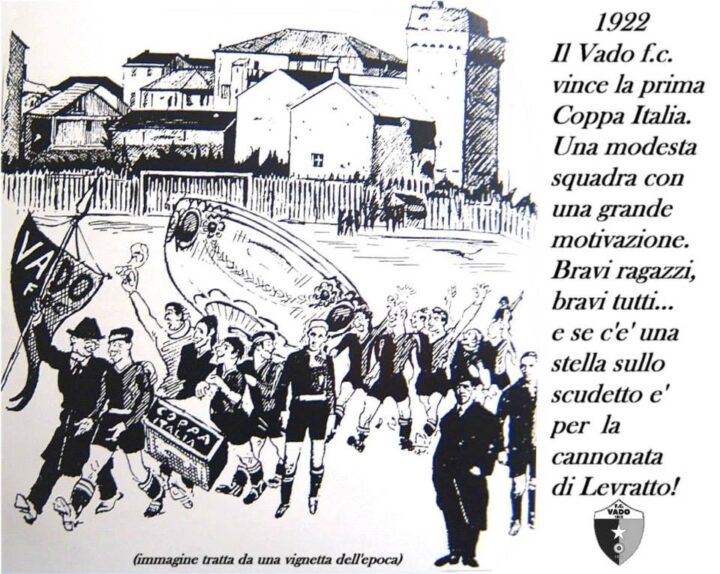

Italy’s Coppa Italia and uneven beginnings

Italy’s experience was less straightforward. The Coppa Italia was launched in 1922, but early editions struggled for consistency and prestige. Clubs prioritised regional leagues and national finals.

Yet even in its irregularity, the cup hinted at potential. Matches drew curiosity. Knockout drama appealed to supporters beyond traditional rivalries.

By the end of the decade, as Italy moved toward a unified league system, the Cup’s importance grew conceptually, even if its full cultural weight would arrive later. The 1920s planted the idea that knockout competition could sit alongside league football meaningfully.

Central Europe’s cup traditions

In Austria, cup competitions such as the ÖFB-Cup, introduced in 1918, gained significance during the 1920s. With Vienna dominating league football, the Cup offered unpredictability.

Matches between Rapid Wien, Austria Wien, and provincial sides carried narrative tension. The Cup became a space where tactical caution gave way to urgency.

In Hungary, similar dynamics played out. Knockout competitions provided contrast to league dominance by Budapest clubs, allowing regional teams moments of prominence.

The Cup’s value lay in interruption.

Scotland and continuity

Scotland’s Scottish Cup mirrored England’s experience. Though older, its cultural gravity deepened in the 1920s as industrial communities treated Cup ties as civic events.

Finals between clubs like Celtic and Rangers attracted massive attention, but so did early-round ties involving smaller sides. The Cup preserved football’s connection to locality even as leagues professionalised.

It reminded supporters that football still belonged to places, not just institutions.

South America’s knockout passion

In South America, league football dominated weekends, but knockout competitions shaped prestige.

In Argentina, the Copa de Competencia and Copa Ibarguren drew intense interest. These matches, often between league champions or regional winners, carried symbolic weight beyond silverware.

Uruguay’s Copa de Honor and Copa Competencia served similar roles, offering high-stakes encounters that reinforced rivalries between Nacional and Peñarol.

The Cup format suited South American football culture: dramatic, decisive, emotional.

Why cups mattered differently

Leagues rewarded consistency. Cups rewarded moments. In the 1920s, as league systems stabilised, supporters needed spaces where unpredictability survived.

Cups provided that. They allowed underdogs belief. They compressed seasons into afternoons. They made football feel urgent again.

Importantly, they created shared national calendars. Cup finals became dates everyone recognised.

The social dimension

Cups mattered because they were accessible. Tickets were cheaper. Matches were often played at neutral venues. Entire towns travelled.

In France and England, Cup finals became social events attended by families, not just regular supporters. The competition belonged to the public as much as to clubs.

This inclusivity distinguished cups from leagues.

Legacy of the 1920s

By the end of the decade, national cups were no longer optional extras. They were institutions.

Even where formats changed, the idea endured: football needed moments that transcended tables and seasons. The Cup provided that space.

Modern football’s obsession with knockout drama has roots not in television scheduling, but in the 1920s, when Cups learned how to matter.