Stadiums beyond sport

By the 1920s, football grounds had ceased to be improvised enclosures. They were no longer just places where matches happened. Across Europe and South America, stadiums became civic statements — expressions of pride, ambition, and belonging. Built from concrete and steel, they reflected how cities saw themselves and how nations wanted to be seen.

Football grounds became monuments not because of decoration, but because of use. They gathered tens of thousands regularly, shaped urban routines and turned football into a public institution.

The interwar building impulse

The decade followed devastation. Cities rebuilt infrastructure, housing, and identity after the First World War. Football benefited from this momentum. Municipal authorities recognised that stadiums were not luxuries but gathering spaces capable of unifying fractured populations.

Unlike earlier grounds, often owned privately or attached to pubs and factories, 1920s stadiums were planned deliberately. Capacity, access, and symbolism mattered.

Concrete replaced wood. Permanence replaced improvisation.

Wembley and the national stage

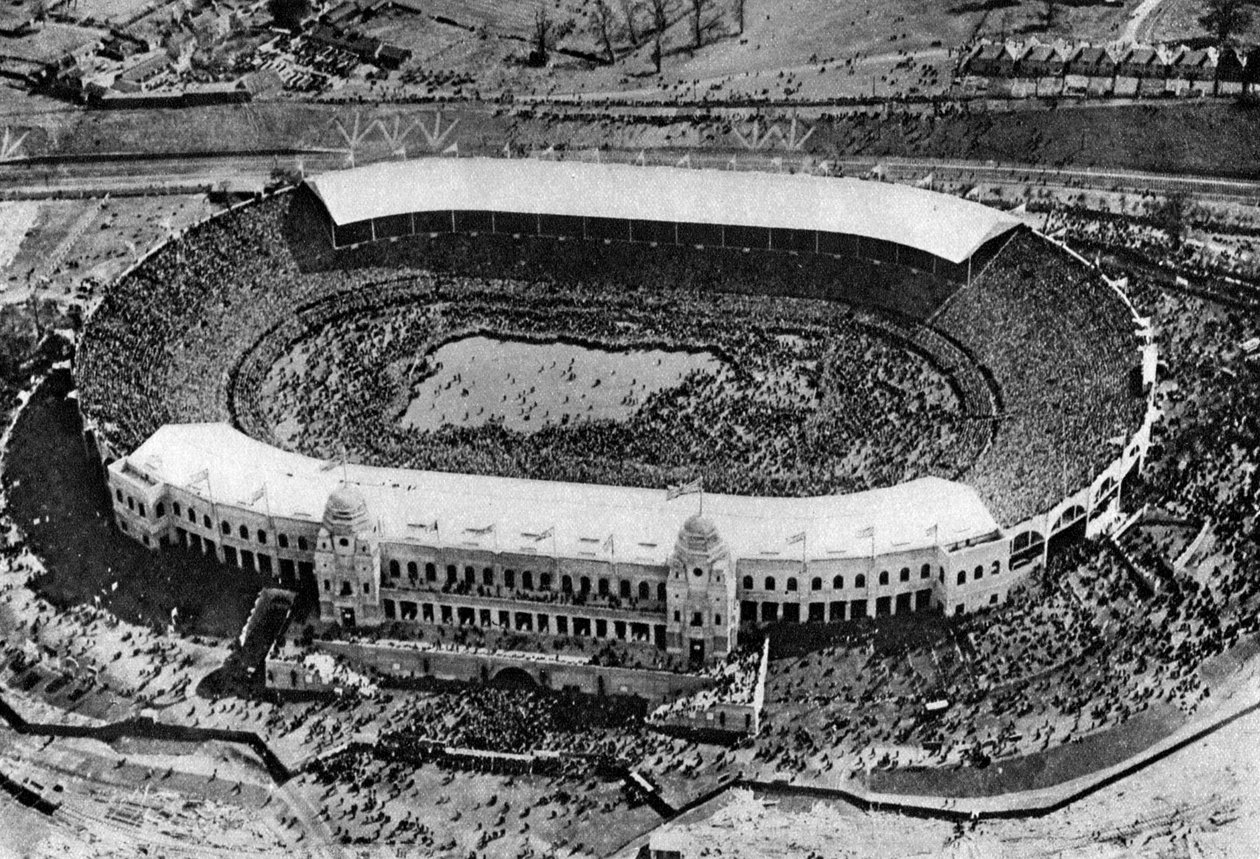

No stadium symbolised this shift more clearly than Wembley Stadium in London. Opened in 1923 for the British Empire Exhibition, Wembley was not built exclusively for football, but football quickly claimed it.

The FA Cup Final transformed Wembley into a national ritual. The 1923 final between Bolton Wanderers and West Ham United drew crowds so large they spilled onto the pitch, embedding the stadium instantly into public consciousness.

Wembley mattered because it centralised the game. It offered England a single ceremonial space, where football intersected with monarchy, ceremony, and mass attendance. The twin towers were not decorative; they were declarative.

Football now had a capital.

Central Europe and municipal pride

In Vienna, football grounds mirrored the city’s cultural confidence. The Hohe Warte, home of First Vienna FC, expanded during the 1920s into one of Europe’s largest stadiums, capable of hosting crowds exceeding 80,000. Its terraced hillside integrated football into the urban landscape rather than isolating it.

Vienna treated football architecturally, not commercially. Stadiums were places to observe modern life unfolding, where sport, culture, and civic identity overlapped.

Similarly, in Budapest, grounds used by MTK Budapest and Ferencváros reflected the city’s embrace of football as an intellectual and communal pursuit. These were not neutral venues. They expressed values of organisation, modernity, and belonging.

Italy’s stadiums and the state

In Italy, football architecture became entangled with politics. As the Fascist regime consolidated power in the late 1920s, stadium construction took on ideological weight.

The Stadio Nazionale del PNF in Rome, opened in 1929, was explicitly political. Its scale and symmetry reflected state authority. Football crowds were not just spectators; they were participants in public display.

Yet even before overt politicisation, Italian cities invested heavily in football grounds. Clubs like Juventus, Internazionale, and Genoa played in venues increasingly tied to municipal ambition.

Stadiums became stages where football, nationalism, and spectacle converged.

Germany’s functional monuments

Germany’s approach was less ceremonial, but equally significant. The 1920s saw the expansion of large multi-purpose stadiums such as Deutsches Stadion projects and major municipal sports parks in cities like Berlin and Nuremberg.

Clubs such as 1. FC Nürnberg benefited from grounds designed to host mass participation events, reflecting the Weimar Republic’s emphasis on physical culture and collective activity.

German stadiums were civic in function rather than symbolism. They represented order, planning, and scale.

South America’s urban cathedrals

In Buenos Aires and Montevideo, football grounds became neighbourhood anchors. Clubs were inseparable from their districts.

Boca Juniors’ stadium at Brandsen y Del Crucero, an early iteration of what would later become La Bombonera, reflected the club’s working-class roots. River Plate, by contrast, began positioning itself as a symbol of modernity and aspiration.

In Montevideo, Estadio Centenario would open in 1930, but its conception belonged firmly to the 1920s. Planned as a national monument for the first World Cup, it represented Uruguay’s belief that football expressed the nation itself.

The stadium was designed not merely to host matches, but to declare arrival.

Stadiums and the weekly ritual

What made these grounds monumental was repetition. Matches were weekly events. Supporters walked the same routes, stood in the same sections, and occupied shared space consistently.

Stadiums shaped urban rhythms. Trams ran differently on matchdays. Shops adjusted hours. Entire districts synchronised around football.

Architecture reinforced habit, and habit created meaning.

Mass participation without intimacy

Unlike modern arenas, 1920s stadiums prioritised capacity over comfort. Terraces dominated. Seats were limited. Standing crowds created density, noise, and collective identity.

This lack of comfort was not accidental. Football was not yet entertainment designed for consumption. It was participation. Supporters did not attend silently; they contributed to atmosphere.

The stadium was not a product. It was a public forum.

Belonging and exclusion

Civic monuments also reflected social boundaries. Stadiums were often segregated by class, sometimes by gender. Access depended on geography, income, and time.

Yet they remained more accessible than many cultural institutions. Entry prices were relatively low. Visibility was communal. Football grounds allowed people to occupy civic space who were excluded elsewhere.

This partial inclusivity strengthened their symbolic power.

Why the 1920s mattered

Earlier grounds existed, but they were provisional. The 1920s introduced the idea that football deserved permanent architecture. Cities invested because they believed football would endure.

That belief proved correct.

Modern stadium debates about identity, ownership, and public funding all trace back to this decade, when football grounds became civic commitments rather than temporary solutions.

What remains

Many 1920s stadiums have been rebuilt, relocated, or demolished. Yet their legacy persists. Football is still anchored in place. Clubs are still identified with districts. Matches still reorganise cities for a few hours at a time.

The 1920s taught football how to inhabit space publicly. Stadiums became monuments not to victory, but to gathering.

They marked the moment football stopped being just a game and became a civic fact.