Control after chaos

By the 1950s, football had returned to normality in appearance. Leagues were stable again. International fixtures resumed. Crowds filled grounds across Europe and South America. Yet beneath that surface, the game carried unresolved tension. Matches were faster, more physical, and increasingly tactical. Authority on the pitch mattered more than ever.

The decade marked a turning point. Referees, once peripheral figures expected simply to keep order, became central to football’s credibility. The 1950s did not invent officiating problems, but they forced the sport to confront them.

Before consistency

Prior to the Second World War, refereeing standards varied widely. Laws of the game existed, but interpretation was local. In England, physical contact was tolerated. In Italy, games were slower and more tactical. In South America, improvisation and flair often clashed with European expectations.

Referees were typically part-time, drawn from domestic associations, with little international coordination. A match officiated in Budapest or Buenos Aires could feel like a different sport from one refereed in Birmingham or Milan.

As football globalised after 1945, these differences became harder to ignore.

The post-war game accelerates

The 1950s game was quicker and more demanding. Tactical systems such as Hungary’s fluid attacking shape, Italy’s emerging defensive organisation at clubs like AC Milan and Inter, and England’s lingering WM system placed greater strain on officials.

Players like Ferenc Puskás, Alfredo Di Stéfano, Gunnar Nordahl, and Stanley Matthews operated in tighter spaces at higher speeds. Fouls were harder to judge. Simulation and gamesmanship increased.

Referees were asked to keep control in environments that had outgrown their training.

Authority under pressure

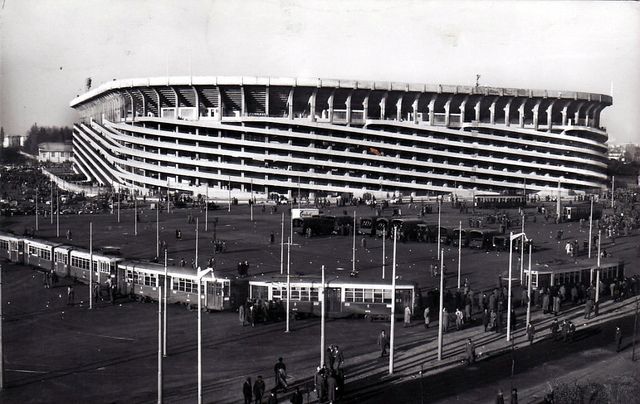

Crowds returned in enormous numbers. Stadiums such as San Siro, Wembley, Estadio Centenario, and Stade de Colombes hosted tens of thousands weekly. Referees worked without assistants, microphones, or video support, relying solely on positioning and judgment.

Authority was fragile. Decisions were contested loudly. Abuse from stands was common. In some leagues, referees faced political and social pressure, particularly in regions where football and identity were closely tied.

Maintaining legitimacy became as important as enforcing rules.

The 1954 World Cup as warning

The World Cup in Switzerland exposed refereeing’s central role. The “Battle of Berne” quarter-final between Hungary and Brazil descended into violence despite officiating efforts. Fouls, retaliation, and post-match fighting highlighted the limits of authority without consistent enforcement.

The final itself raised questions. Hungary’s disallowed equaliser, Germany’s physical approach, and uneven punishment fed debate across Europe. The outcome was accepted, but trust was shaken.

FIFA could no longer ignore officiating as a background issue.

Law standardisation

The 1950s saw renewed emphasis on uniform interpretation. FIFA and the International Football Association Board worked to clarify laws, particularly around offside, dangerous play, and goalkeeper protection.

Referees were encouraged to assert control earlier in matches. Leniency gave way to intervention. Whistles blew more often. Cards did not yet exist, but verbal warnings and dismissals increased.

The aim was not spectacle, but order.

Domestic reforms

National associations followed suit. In England, the FA began formalising referee training and assessment. In Italy, officiating became closely tied to tactical discipline, mirroring Serie A’s evolving identity. In Spain, referees navigated intense regional rivalries involving Real Madrid, Barcelona, and Athletic Bilbao.

In South America, CONMEBOL faced similar challenges as continental competitions expanded. Matches between Argentine and Uruguayan clubs demanded neutral authority to prevent escalation.

Referees were no longer anonymous. Their reputations mattered.

Power without protection

Despite increased responsibility, referees remained poorly protected. They lacked technological support and institutional backing when decisions provoked outrage. Suspensions, demotions, and public criticism were common.

Authority existed, but it was personal rather than structural. A referee’s control depended on confidence and presence as much as rule knowledge.

This imbalance shaped officiating culture for decades.

A quieter transformation

The 1950s did not introduce red cards, VAR, or professional referees. Its contribution was subtler. It established the idea that football’s credibility depended on consistent authority.

Referees were no longer tolerated. They were necessary.

The game accepted that without trusted control, competition lost meaning.

Legacy

By the end of the decade, officiating was still imperfect. Controversy remained part of football. But the expectation had shifted. Matches were judged not only by goals and tactics, but by fairness and control.

That expectation began in the 1950s, when football realised that authority was not an accessory to the game, but one of its foundations.