A continental tournament few could see

For much of its early existence, the Copa Libertadores was a competition defined by absence. Absence of cameras, absence of live broadcasts, absence of a shared global audience. Founded in 1960, the tournament brought together South America’s most powerful clubs at a time when their reputations travelled faster than the images of their football. Outside the continent, the Libertadores existed largely through newspaper reports, radio commentary, and the testimony of visiting players.

This absence mattered. Without global television, the Libertadores developed its own ecosystem — one shaped by distance, suspicion, myth, and intensity. Clubs like Peñarol, Santos, Estudiantes, Independiente, and Nacional built continental legacies long before most European fans could reliably watch them. The competition became feared rather than familiar.

CONMEBOL’s answer to Europe

The Copa Libertadores was conceived partly as a response to the European Cup. CONMEBOL wanted a continental championship that reflected South America’s club power, especially after Uruguay’s 1950 World Cup triumph and Brazil’s growing confidence. Peñarol of Montevideo, led by players such as Alberto Spencer and Pedro Rocha, became early standard-bearers, winning the first two editions in 1960 and 1961.

But unlike Europe, South America lacked stable broadcast infrastructure. Matches between Peñarol and Olimpia, or Santos and Universidad de Chile, were rarely filmed beyond highlights. Stadiums like the Estadio Centenario, La Bombonera, and the Estádio do Maracanã were theatres known more by reputation than imagery.

This allowed the Libertadores to evolve in relative isolation, governed by local expectations rather than external scrutiny.

The age of intimidation

Without global television, behaviour went largely unchecked. The Libertadores of the 1960s and early 1970s became notorious for its atmosphere, physicality, and psychological warfare. Visiting teams faced hostile crowds, uneven refereeing, and conditions designed to unsettle rather than entertain.

Estudiantes de La Plata, under coach Osvaldo Zubeldía, mastered this environment. Their back-to-back titles in 1968, 1969, and 1970 were achieved through meticulous preparation, set-piece innovation, and a willingness to push boundaries. Players like Carlos Bilardo and Raúl Madero became symbols of a ruthless era.

In Europe, these stories filtered through slowly. When Estudiantes faced Manchester United in the 1968 Intercontinental Cup, the shock was not just tactical — it was cultural. European clubs were encountering a competition they did not fully understand.

Santos and the unseen greatness

Perhaps no club suffered more from the lack of global television than Santos. Between 1962 and 1963, the Brazilian side won consecutive Libertadores titles, led by Pelé at his physical and creative peak. Alongside him were Coutinho, Pepe, and Zito, forming one of club football’s most formidable attacks.

Yet much of Pelé’s Libertadores brilliance survives only in fragments. Goals against Benfica are remembered more clearly than goals against Peñarol or Boca Juniors, not because of quality, but because of coverage. Santos toured Europe extensively, partly to make money, but also to be seen.

The Libertadores, paradoxically, was where Pelé was most dominant — and least visible.

Travel, fatigue, and imbalance

Pre-television Libertadores campaigns were logistically brutal. Teams crossed continents by plane and bus, often with minimal recovery time. Argentine clubs travelling to Colombia, or Chilean sides visiting Brazil, faced not only altitude and climate but disjointed scheduling.

There was no commercial imperative to standardise kick-off times or conditions for broadcast audiences. Matches were played when they could be played, often late at night, often midweek, often amid domestic congestion.

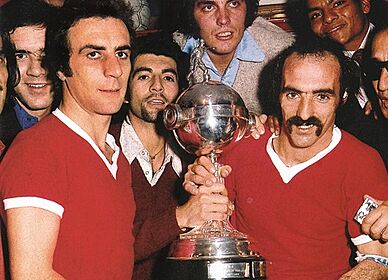

This rewarded squads with depth, experience, and adaptability. Clubs like Independiente, who won four consecutive titles between 1972 and 1975, thrived in this chaos. Their dominance was built on institutional knowledge as much as talent.

National pride over global appeal

Before television money reshaped priorities, Libertadores success was about prestige rather than profit. Winning the competition elevated clubs domestically and regionally, reinforcing national football identities. For Uruguay and Argentina, it was a reaffirmation of continental leadership. For Brazil, it became a statement that club football could match international success.

Matches were political as well as sporting. Military regimes, particularly in Argentina during the late 1960s and 1970s, viewed continental football as a projection of national strength. Stadiums became stages for symbolism, not spectacles for overseas consumption.

This inward focus made the Libertadores intensely meaningful to those inside it — and largely invisible to those outside.

The slow arrival of cameras

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, television began to encroach. Brazilian networks invested more heavily. Argentine broadcasts improved. The Intercontinental Cup gained a wider audience, indirectly raising the profile of Libertadores champions.

Yet even then, coverage was fragmented. European audiences still encountered the competition sporadically, often through VHS recordings or late-night highlight shows. Diego Maradona’s brief Libertadores appearance with Boca Juniors in 1981, culminating in victory over Cruzeiro, was more felt than seen.

Global television would eventually sanitise, commercialise, and standardise the Libertadores. But in doing so, it would also remove some of its mystery.

What was lost and what remained

The pre-television Copa Libertadores was harsher, less polished, and often deeply flawed. But it was also intimate, locally grounded, and emotionally extreme. Players were known by reputation, clubs by rumour, stadiums by fear.

Today’s tournament reaches millions across continents. Yet the foundations of its identity were laid in an era when few outside South America could watch — only imagine.

That imagined Libertadores, shaped by stories rather than screens, remains central to its mythology.