Before the World Cup mattered

For the first half of the twentieth century, the Olympic football tournament was not a sideshow. It was the centrepiece. Before FIFA’s World Cup became the sport’s defining competition, Olympic football represented the highest international stage available to most players, nations, and spectators. Winning Olympic gold meant global recognition, tactical validation, and national prestige.

Between 1908 and 1936, Olympic football was effectively the world championship of the game. The World Cup, founded only in 1930, arrived late to a structure already dominated by the Olympics — and for a time, struggled to replace it.

Amateurism and legitimacy

The Olympic tournament benefited from a powerful idea: legitimacy through amateurism. In an era when professionalism was viewed with suspicion, Olympic football was seen as pure competition, free from commercial pressure. Nations such as Great Britain, Denmark, Sweden, and Hungary treated Olympic football as their primary international outlet.

Great Britain’s victories in 1908 and 1912, driven largely by amateur English players from clubs like Corinthians, reinforced the idea that Olympic football represented the game’s highest ideals. These tournaments attracted large crowds and serious media attention, particularly in Europe.

FIFA itself initially recognised Olympic winners as de facto world champions. Until the World Cup existed, there was no higher honour.

Uruguay and the shift of power

The decisive moment in Olympic football’s dominance came in the 1920s. Uruguay’s victories at the 1924 Paris Olympics and the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics reshaped football’s geography. Their style, technique, and tactical sophistication stunned European audiences.

Players such as José Leandro Andrade and Héctor Scarone became international stars through Olympic football, not domestic leagues. Uruguay’s 1924 Olympic final against Switzerland drew over 60,000 spectators and was treated as a global event.

These victories mattered so deeply that Uruguay’s Olympic titles directly led to the creation of the World Cup. FIFA awarded Uruguay hosting rights for the inaugural 1930 tournament specifically because of their Olympic success.

At this point, Olympic football was not rival to the World Cup. It was the reason the World Cup existed.

The World Cup arrives, but does not dominate

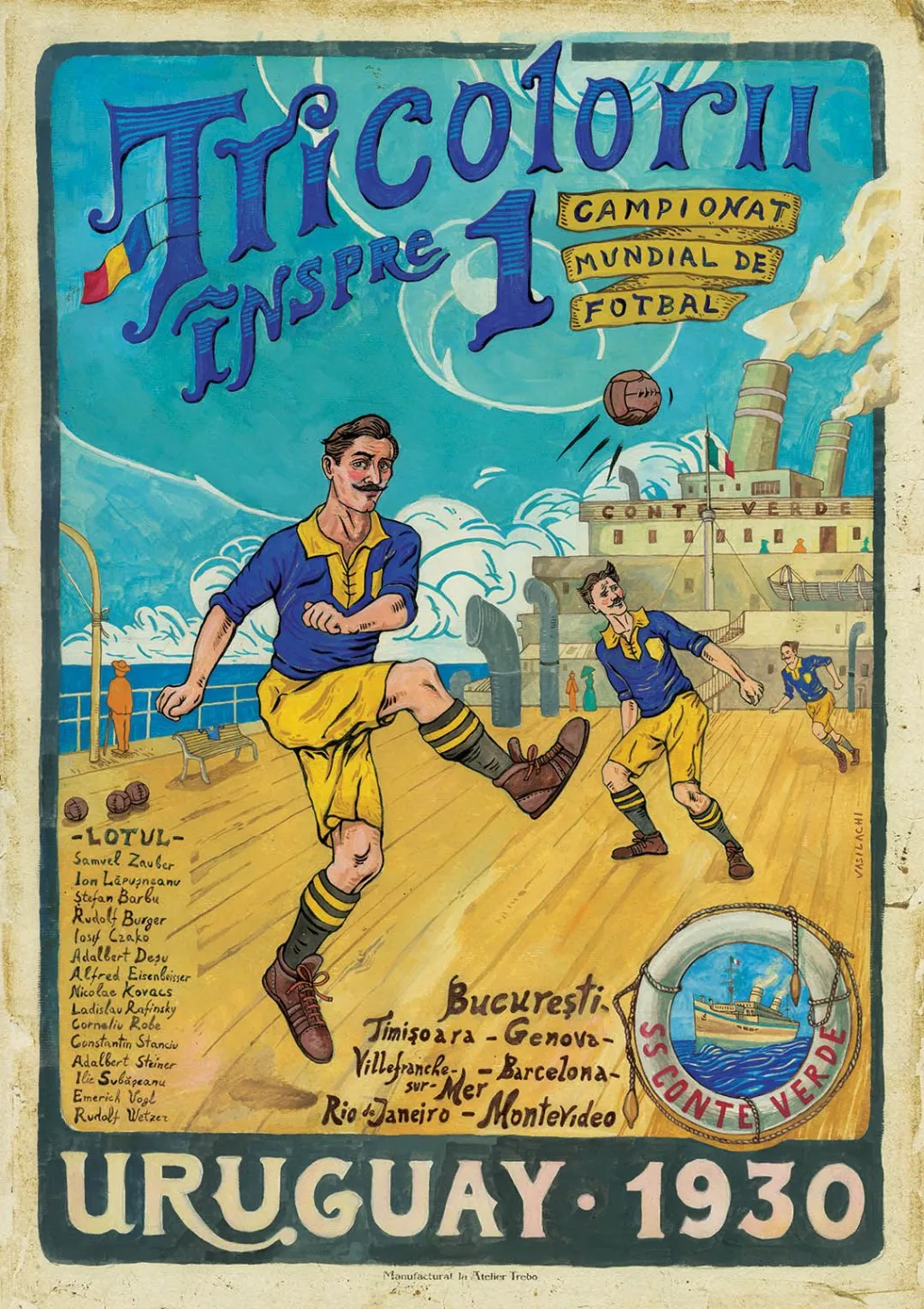

The early World Cups did not immediately eclipse the Olympics. The 1930 World Cup involved only thirteen teams. Travel costs, political tensions, and European reluctance limited participation. In contrast, the Olympic tournament remained familiar, prestigious, and accessible.

The 1934 and 1938 World Cups expanded football’s reach, but Olympic football retained cultural authority. Many fans and federations still viewed Olympic success as equal — if not superior — to World Cup achievement.

The balance did not decisively shift until professionalism entered the equation.

Professionalism breaks the system

Olympic amateur rules gradually undermined the tournament’s credibility. As professional leagues expanded across Europe and South America, Olympic eligibility became increasingly artificial. Strong nations were forced to field weakened sides or exclude their best players entirely.

By the 1936 Berlin Olympics, political interference and eligibility disputes dominated discussion. Italy won gold with a team that closely resembled its professional national side, exploiting loopholes that blurred the amateur line.

The Second World War then halted international football altogether, freezing Olympic football in an unresolved state.

The Cold War revival

After 1948, Olympic football returned in a new form. Eastern Bloc nations, operating under state-sponsored amateurism, dominated the tournament. Countries like Hungary, Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and Czechoslovakia were able to field their strongest players, who were technically amateurs but functionally full-time professionals.

Hungary’s gold medals in 1952 and 1964, featuring players like Ferenc Puskás and later generations shaped by state systems, restored Olympic football’s competitive relevance. Yugoslavia’s consistency throughout the 1950s and 1960s further reinforced the tournament’s prestige.

For many nations excluded or marginalised in World Cup qualification, Olympic football remained the most meaningful international competition available.

A different kind of world stage

Olympic football rivalled the World Cup not because it mirrored it, but because it offered something different. It rewarded organisation over celebrity, continuity over star power. Smaller nations could build long-term squads and challenge traditional powers.

African and Asian teams, often denied World Cup access or allocation, treated Olympic qualification as a primary objective. Egypt’s appearances, North Korea’s success in 1976, and Iraq’s qualification in 1988 all reflected this shift.

The Olympic tournament became a stage for football outside Europe and South America to assert itself.

The under-23 rule changes everything

The decisive break came in 1992, when FIFA introduced the under-23 rule for Olympic football, later allowing three over-age players per squad. This redefined the tournament’s identity permanently.

Olympic football was no longer competing with the World Cup. It became a developmental competition, a bridge between youth and senior football. While still prestigious, it ceased to be a measure of global supremacy.

Nations began prioritising the World Cup exclusively. Olympic gold became an achievement — not a defining one.

What rivalry really meant

When Olympic football rivalled the World Cup, it did so because football itself had not yet decided what mattered most. Before global television, commercial sponsorship, and qualification structures, legitimacy was shaped by tradition, ideology, and opportunity.

The Olympics offered visibility, authority, and international recognition at a time when alternatives were limited. The World Cup eventually surpassed it not through superiority, but through timing, professionalism, and control.

Olympic football did not decline because it failed. It declined because football outgrew it.

Why it still matters

Understanding Olympic football’s former status changes how early football history is read. Titles won before 1930 were not lesser achievements. They were central ones.

For Uruguay, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and others, Olympic football was the stage on which national football identity was forged. The World Cup inherited that authority — it did not invent it.