A tournament born outside football

The Inter-Cities Fairs Cup began in 1955 not as a UEFA competition, nor even strictly as a football one. It was created to accompany international trade fairs, linking cities rather than clubs and tying the sport to post-war economic recovery. Early entrants were not teams in the modern sense but city selections, such as London XI, Barcelona XI, and Basel XI, assembled to represent commercial centres rebuilding their place in Europe.

In a continent still reshaping itself after the Second World War, the Fairs Cup reflected a broader desire for connection. Football provided the spectacle, but the motivation was cultural and economic as much as sporting. That unusual origin would shape the competition’s identity for its entire lifespan.

From city teams to real clubs

The first editions were irregular and slow, sometimes stretching across several years. Matches were sporadic, travel was complicated, and the concept itself was fluid. But by the early 1960s, the tournament began to resemble something recognisable. City teams were phased out, replaced by established clubs such as FC Barcelona, Valencia, AS Roma, and Dinamo Zagreb.

This shift mattered. It transformed the Fairs Cup from a novelty into a proving ground. Clubs that were strong domestically but excluded from the European Cup suddenly had continental football of their own. For teams finishing second, third, or fourth in competitive leagues, this was the only route into Europe.

A home for the almost-elite

The European Cup was exclusive by design, reserved for league champions. The Cup Winners’ Cup was similarly narrow. The Fairs Cup filled the gap. It became the competition for ambitious clubs just outside the elite bracket, offering European exposure without requiring domestic dominance.

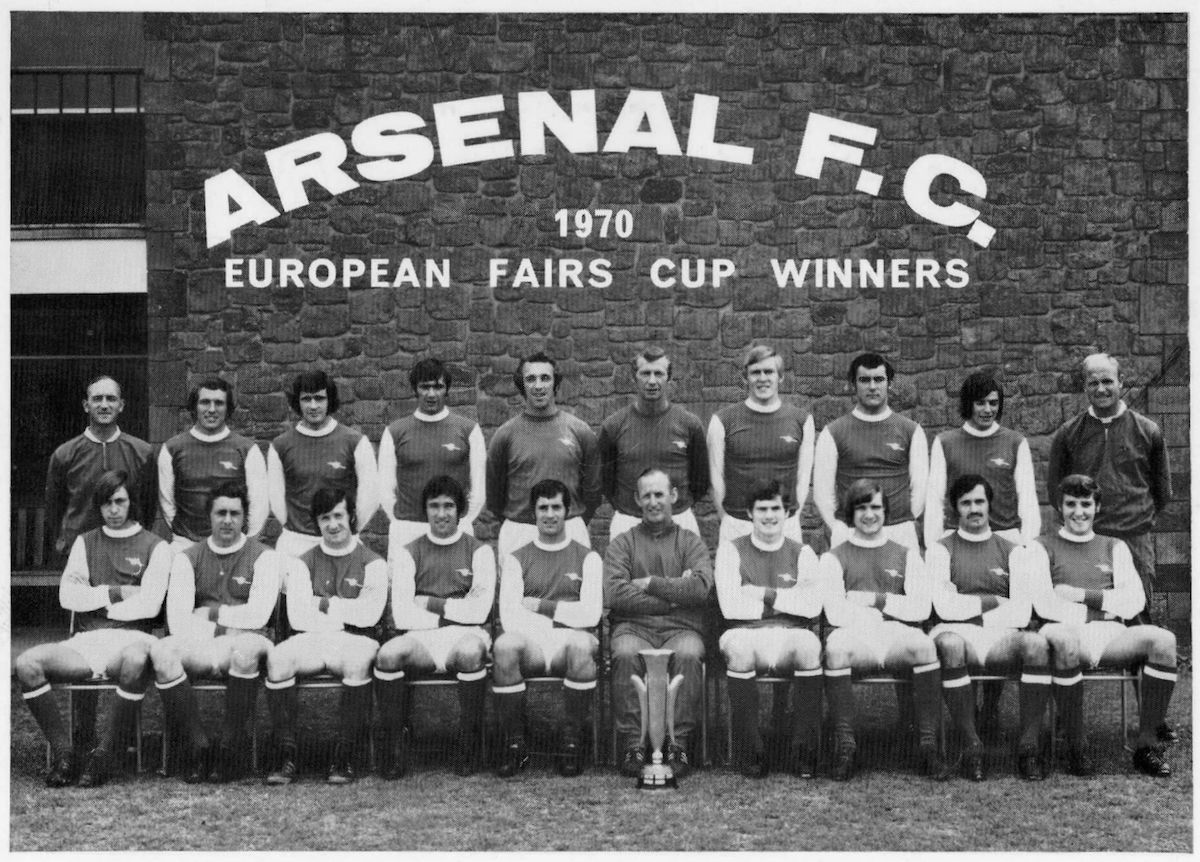

Clubs like Leeds United, Arsenal, Inter Milan, and Ferencváros used the Fairs Cup to test themselves internationally. For Leeds, winners in 1968 and 1971, it was arguably the competition that defined Don Revie’s side in Europe. Arsenal’s 1970 triumph marked the club’s first European trophy, a milestone often overshadowed by later success.

The Fairs Cup created a European middle class, allowing clubs to build reputations, revenue, and experience long before qualification pathways expanded.

Styles colliding before standardisation

Because it operated outside UEFA control for much of its existence, the Fairs Cup lacked strict standardisation. Rules varied, refereeing styles differed, and scheduling was often improvised. This created chaotic, sometimes hostile environments, particularly in matches involving clubs from Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, and Britain.

British clubs encountered continental tactics earlier and more frequently through the Fairs Cup than through the European Cup. Matches against clubs like Juventus, Barcelona, and Red Star Belgrade exposed English sides to pressing, technical midfield play, and tactical discipline that domestic football rarely demanded.

These encounters mattered. They forced adaptation, even if reluctantly, and laid groundwork for later European competitiveness.

The Spanish dominance

No nation embraced the Fairs Cup quite like Spain. FC Barcelona won it three times, Valencia twice, and Real Zaragoza once. Spanish clubs treated the competition seriously, often fielding full-strength sides while others rotated or prioritised domestic fixtures.

For Barcelona, in particular, the Fairs Cup became a defining European stage during periods when the club fell short in the European Cup. Players like Luis Suárez, Josep Maria Fusté, and later Carles Rexach featured heavily in Fairs Cup campaigns that sustained the club’s continental relevance.

The competition allowed Spanish football to project itself internationally at a time when domestic success did not always translate into European trophies.

Political borders and football bridges

The Fairs Cup also crossed political lines more freely than many competitions of its era. Clubs from Yugoslavia, Hungary, Poland, and Czechoslovakia regularly participated, facing Western European sides at a time when Cold War divisions shaped almost every other aspect of life.

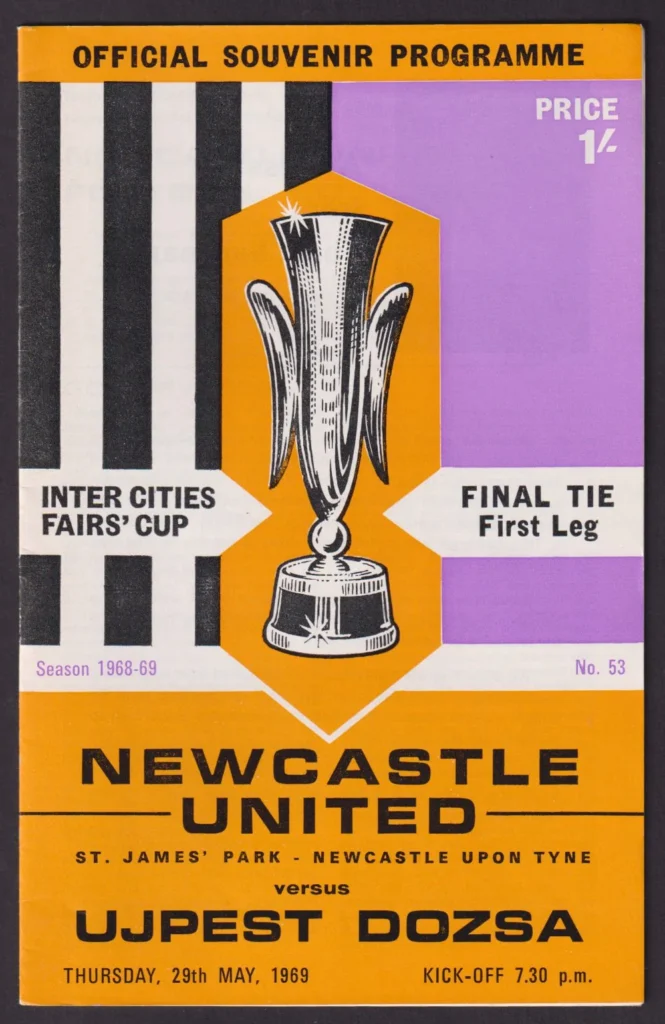

Matches involving Dinamo Zagreb, Újpesti Dózsa, and Spartak Brno were not just sporting events but rare points of contact. Football grounds became spaces where ideologies briefly gave way to competition. The Fairs Cup did not erase political realities, but it offered continuity and dialogue through sport.

For players and supporters alike, these fixtures carried a significance that extended beyond results.

A competition without memory

Despite its importance, the Fairs Cup suffers from an identity problem. It is not officially recognised by UEFA as a major trophy, and its records are often excluded from modern honours lists. When UEFA replaced it with the UEFA Cup in 1971, the transition was clean administratively but messy historically.

The final Fairs Cup match, a playoff between Leeds United and Barcelona to decide permanent ownership of the trophy, symbolised this ambiguity. Leeds won, the trophy disappeared, and the competition faded without ceremony.

What replaced it was more structured, more commercial, and more visible. What was lost was a bridge between eras.

Why it still matters

The Inter-Cities Fairs Cup mattered because it normalised European football for clubs outside the champions. It taught teams how to travel, adapt, and compete internationally. It introduced supporters to foreign opponents before continental football became routine.

Many of today’s assumptions about European qualification, secondary tournaments, and continental identity trace their roots to the Fairs Cup. The Europa League, for all its modern trappings, owes more to this obscure competition than is usually acknowledged.

The Fairs Cup was imperfect, unofficial, and often forgotten. But without it, European football would have evolved far more slowly, and far more unevenly.