When the league refused to stop

When the Iran–Iraq War began in September 1980, few imagined it would last eight years. Fewer still imagined that Iraqi football would continue almost uninterrupted. Yet while artillery thundered along the eastern border and cities absorbed the strain of total war, domestic football in Iraq carried on — altered, constrained, but stubbornly alive.

This was not football as escapism alone. It was football as signal: that the state endured, that daily life could be organised, that crowds could still gather. The Iraqi league did not become irrelevant during wartime. It became political, symbolic, and, in some cases, dangerous.

A league under state gravity

By the early 1980s, Iraqi football was already deeply entangled with the state. Clubs like Al-Shorta (police), Al-Jaish (army), and Al-Talaba (students) reflected institutional power rather than civic identity. This structure proved oddly resilient once war began.

While civilian industries stalled, state-backed clubs retained resources. Travel was restricted, but teams moved with military coordination. Fixtures were rearranged, not cancelled. Matches in Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul were shifted around air-raid warnings rather than postponed indefinitely.

The league’s continuation was not organic. It was deliberate.

Baghdad as a controlled stage

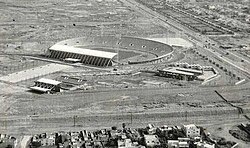

Baghdad became the centre of Iraqi football during the war. Stadiums like Al-Shaab Stadium, opened in 1966, hosted matches under heightened security. Attendance fluctuated — sometimes sparse, sometimes unexpectedly full — depending on bombing cycles and transport access.

Crowds were quieter. Celebrations were shorter. Matches ended earlier. But football offered something few other public spaces could: collective normality.

For young Iraqis, especially those approaching conscription age, football grounds were places where time briefly behaved as it had before the war.

Players between training and the front

Many Iraqi players were eligible for military service. Some were protected; others were not.

Conscription did not stop entirely for footballers. Players missed matches due to service, training camps, or injuries sustained outside football. Squads became unstable. Youth players were promoted quickly. Veterans extended careers longer than planned.

Yet Iraq still produced a competitive national team core during this period.

Players like Hussein Saeed, Ahmed Radhi, and Adnan Dirjal emerged or consolidated reputations while the war continued. Training schedules adapted around power cuts and travel restrictions. International friendlies were rare, but internal competition remained fierce.

Football did not pause development — it distorted it.

The national team as wartime asset

Internationally, Iraq’s national team became a political instrument. Qualification for the 1984 Olympics and later success in the 1988 Seoul Olympics — where Iraq reached the quarter-finals — were framed domestically as proof of national strength.

Matches were broadcast with heavy commentary emphasis on resilience and unity. Victories were celebrated publicly. Defeats were downplayed or contextualised as heroic efforts.

The team’s qualification for the 1986 World Cup in Mexico was the ultimate wartime football achievement. Iraq lost all three group matches, but merely appearing on football’s largest stage during an ongoing war carried enormous symbolic value.

The message was clear: Iraq could still compete, still travel, still belong.

Basra and the football that faded

Not all cities experienced wartime football equally. Basra, closest to the front line, suffered the most. Clubs struggled to host matches. Infrastructure degraded. Players relocated to Baghdad-based teams or left football entirely.

Some regional competitions effectively collapsed, their absence masked by continued national league play. This uneven survival distorted Iraqi football geography, concentrating power in the capital and hollowing out provincial systems.

The effects would linger long after the ceasefire.

Football under fear

Air-raid sirens were part of matchday life. Matches paused. Crowds dispersed briefly, then returned. Players learned to keep focus while scanning the sky.

There are accounts of matches completed under blackout conditions, floodlights dimmed or turned off early. Radios sometimes replaced scoreboards. Security forces were visible at every fixture.

This was football played under constant awareness that the game could be interrupted by forces far beyond it.

Isolation from the wider game

The war isolated Iraqi football tactically and culturally. Coaches had limited exposure to European developments. Player transfers abroad were rare. Youth systems stagnated compared to emerging academies elsewhere.

Yet isolation also reinforced a distinct style: physical, disciplined, defensively organised. Iraqi teams played pragmatically, shaped by scarcity and uncertainty rather than innovation.

When Iraq faced international opponents, the contrast was stark — but not always unfavourable.

After the ceasefire

When the war ended in 1988, Iraqi football did not immediately recover. Infrastructure was damaged. Talent pools were uneven. The next decade would bring new sanctions, new isolation, and new disruptions.

In retrospect, the 1980s were not a lost decade for Iraqi football — but they were a distorted one. Progress occurred, but under pressures that shaped careers, clubs, and identities in unusual ways.

Football survived the war, but it did not escape it.

Why it still matters

Iraqi football during the Iran–Iraq War challenges the idea that sport simply stops in times of conflict. It shows how football can be preserved, manipulated, and sustained as part of national endurance.

These matches were not footnotes. They were lived experiences — played, watched, and remembered by people navigating a war that defined their lives.

Football did not distract Iraq from war. It existed inside it.