Living in the long pause

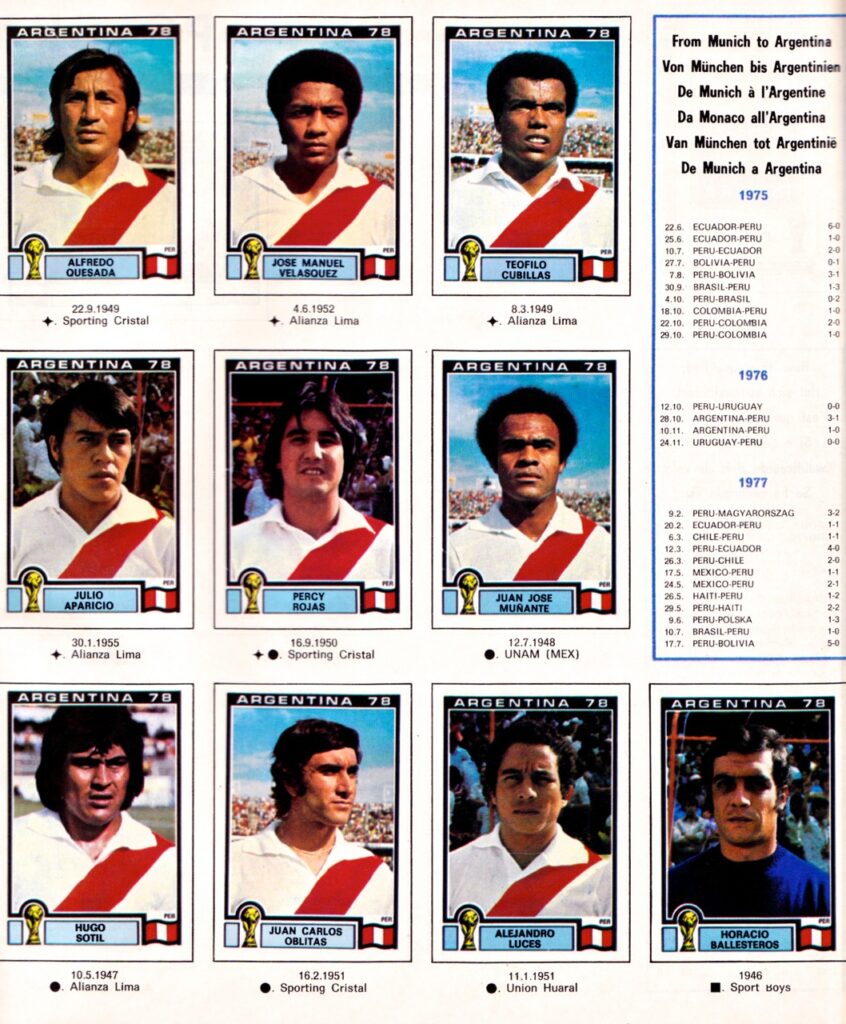

Peruvian football is often remembered in bursts. The elegant teams of the 1970s, led by Teófilo Cubillas, Héctor Chumpitaz, and César Cueto. Then, much later, the revival that carried Paolo Guerrero, Jefferson Farfán, and Christian Cueva back to the World Cup in 2018. Between those two peaks lies a long, uneasy stretch that is rarely examined: the decades when Peru remained visible, talented, and culturally rich, yet permanently unfinished.

This was not an era of collapse. It was an era of waiting.

After Mexico 1970 and Argentina 1978

The Peru side of 1970 and 1978 established a myth that would become both inheritance and burden. They played with confidence, technical fluency, and continental authority. Clubs like Alianza Lima, Universitario, and Sporting Cristal supplied players who were tactically loose but individually gifted.

When that generation aged out, there was no structural replacement. Youth development remained informal. Domestic coaching stagnated. The expectation, however, did not fade. Peru were still supposed to play beautifully — even when results no longer supported it.

Domestic football without momentum

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the Peruvian Primera División struggled to modernise. Financial instability became routine. Clubs relied heavily on short-term signings and local loyalty rather than long-term planning.

Alianza Lima remained culturally dominant but inconsistent. Universitario oscillated between title challenges and crisis. Sporting Cristal, backed by stronger administration, were often the most stable, yet even they struggled to translate domestic success into continental relevance in the Copa Libertadores.

The league produced footballers, but rarely platforms.

Talent without pathways

Peru never lacked players. It lacked trajectories. Footballers like Nolberto Solano, José del Solar, Juan Reynoso, and Claudio Pizarro emerged in isolation rather than as part of a coherent generation. Some left early for Europe. Others stagnated domestically. Few returned at their peak.

Solano’s career at Newcastle United and Aston Villa was admired abroad but loosely connected to the national team’s fortunes. Pizarro scored freely for Werder Bremen and Bayern Munich, yet struggled to anchor Peru internationally.

Success abroad did not translate into belief at home.

World Cup absence as normality

After qualifying for Spain 1982, Peru disappeared from the World Cup stage for 36 years. Near misses became familiar. Campaigns ended not in dramatic failure, but in quiet elimination.

The qualifiers for France 1998 and Germany 2006 were particularly symbolic. Peru were competitive, technically capable, and tactically fragile. Matches were lost late. Discipline faltered. Momentum evaporated.

The absence became routine — and routine became identity.

Coaching without continuity

One of the defining features of this in-between era was instability on the bench. Foreign coaches arrived with short mandates. Local coaches lacked authority or institutional backing. Philosophies shifted every cycle.

There was no long-term plan to reconcile Peru’s technical tradition with modern athletic demands. Instead, each qualifying campaign reset expectations without resetting structure.

The national team existed in permanent transition.

The emotional weight of style

Unlike more pragmatic football nations, Peru carried an aesthetic obligation. Playing ugly felt like betrayal. Playing beautifully and losing felt familiar.

This cultural expectation trapped generations of players. Defensive solidity was viewed suspiciously. Tactical discipline was mistaken for caution. The past hovered over every match.

Peru were not allowed to simply rebuild. They were expected to remember.

Copa América as temporary relief

The Copa América offered brief escapes. Peru finished runners-up in 1975, then later reached the semi-finals in 1997 and 2001. These tournaments revived optimism without resolving structural issues.

Short-format success masked long-term fragility. Once qualifiers resumed, reality returned.

Why the middle years matter

Peru between golden generations matters because it explains why revival was so difficult — and why it eventually meant so much. The years of drift preserved identity without protecting competitiveness. They produced players with technique but limited collective belief.

When qualification finally came in 2018, it felt less like a breakthrough and more like release.

Those decades of waiting shaped modern Peruvian football as deeply as any triumph.

A football culture that endured

Despite underachievement, Peruvian football never lost its cultural gravity. Stadiums remained emotional. Club rivalries endured. The idea of football as expression survived administrative failure.

The country did not forget how it once played. It simply lacked the conditions to do so again.

Why Peru’s pause still resonates

Golden generations define how nations are remembered. The spaces between them define how nations survive.

Peru’s long middle era was not empty. It was formative — a reminder that football history is not built only on peaks, but on endurance.