A game learned through ports and plantations

Football arrived in the Dutch East Indies not as a national project but as a by-product of colonial life. Dutch administrators, soldiers, and merchants brought the game to port cities such as Batavia (Jakarta), Surabaya, and Semarang in the early twentieth century. Matches were initially confined to European clubs like Bataviasche Voetbal Club and Hercules Batavia, played on fields attached to military or plantation compounds. Indigenous participation came slowly, often through schools, dock work, and informal neighbourhood sides that learned the game by watching rather than being invited.

Early organisation and quiet resistance

The founding of PSSI (Persatuan Sepakbola Seluruh Indonesia) in 1930 was a crucial moment. Led by figures such as Soeratin Sosrosoegondo, PSSI was not merely a sporting body but a nationalist statement. At a time when the Dutch KNVB-affiliated competitions excluded most indigenous players, PSSI organised parallel tournaments that prioritised local clubs like Persis Solo, PSIM Yogyakarta, and Persija Jakarta. Football became one of the few spaces where Indonesian identity could be expressed openly, even before independence.

War, interruption, and survival

The Japanese occupation during World War II disrupted organised football almost entirely. Grounds were repurposed, travel was restricted, and many players were conscripted or displaced. Yet football did not disappear. Informal matches persisted in kampongs and military barracks, keeping clubs alive in memory rather than in structure. When independence was declared in 1945, Indonesian football resumed not from strength, but from endurance.

International football without stability

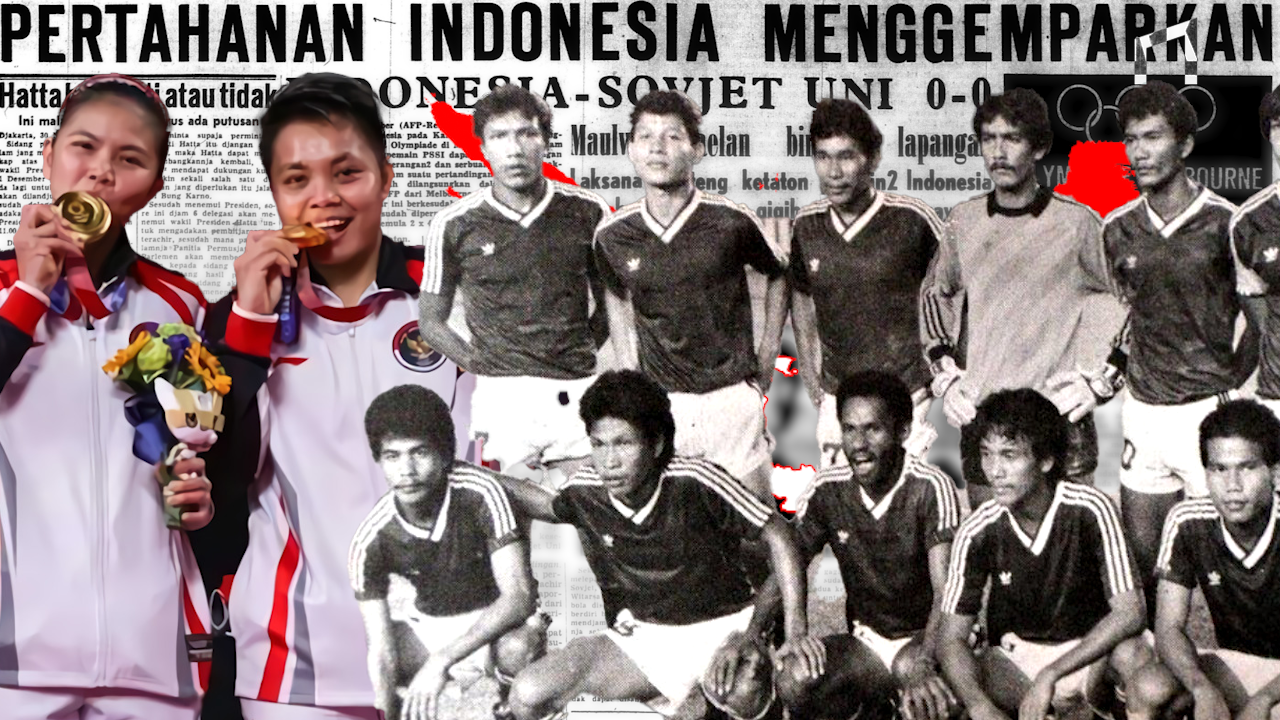

In the late 1940s and 1950s, Indonesia appeared sporadically on the international stage. Their most famous early moment came at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, where they held the Soviet Union to a 0–0 draw before losing the replay. Players like Maulwi Saelan, Ramang, and Sarnadi represented a nation still forming its institutions. These performances hinted at potential, but domestic instability meant there was no system to build on isolated successes.

Domestic football as regional loyalty

For decades, Indonesian football was defined less by national hierarchy and more by regional pride. The Perserikatan league, officially amateur, was organised around city teams rather than privately owned clubs. Matches between Persib Bandung, Persebaya Surabaya, and Persija Jakarta drew huge crowds, often driven by civic identity rather than league position. Stadiums like Gelora Bung Karno and Gelora 10 November became arenas of regional rivalry, but not of professional development.

The long absence of professionalism

While neighbours such as Malaysia and Thailand experimented with semi-professional structures earlier, Indonesia remained resistant. Players often held other jobs. Training schedules were inconsistent. Youth development depended heavily on schools and local associations rather than academies. The lack of a stable professional league meant talent peaked early or drifted away. Indonesian football produced heroes, but rarely systems.

Isolation from Asian competition

Indonesia’s relationship with continental football was inconsistent. Political decisions, including withdrawal from FIFA in the 1960s, limited exposure to Asian tournaments. Even after rejoining, participation in the AFC Asian Cup and Asian Games was irregular. When Indonesian clubs did appear in competitions like the Asian Club Championship, they were usually unprepared for the tactical and physical demands faced by teams from South Korea, Iran, or Japan.

Supporters before success

One paradox defined Indonesian football before its regional rise: enormous support without corresponding results. Supporter groups such as Bobotoh (Persib Bandung) and Bonek (Persebaya Surabaya) emerged long before continental success. Stadiums filled regardless of league quality. Football mattered socially even when it struggled competitively. This culture sustained the game during decades when administration and infrastructure did not.

The fractured 1990s

The introduction of the Liga Indonesia in 1994 merged amateur and semi-professional systems, promising reform. Instead, it exposed deeper problems. Financial instability, match-fixing allegations, and political interference undermined credibility. Clubs appeared and disappeared. Player wages went unpaid. Yet this chaotic decade also produced players like Kurniawan Dwi Yulianto and Bima Sakti, who gained rare experience abroad with Sampdoria and other Asian clubs.

Before dominance, there was patience

Indonesia’s later regional relevance in competitions such as the AFF Championship did not emerge suddenly. It was built on decades of survival without structure, popularity without professionalism, and identity without success. Before dominance, Indonesian football existed as a cultural constant rather than a competitive force. Its foundations were emotional, regional, and political long before they became tactical or administrative.

What the early era left behind

The Indonesia that eventually challenged Southeast Asian neighbours carried scars from this period. Infrastructure gaps, governance issues, and uneven development remained visible. But so did resilience. Football had survived colonial exclusion, war, political withdrawal, and organisational failure. Before regional dominance, Indonesian football learned how to endure, how to matter without winning, and how to belong deeply to its people.

That endurance, more than any trophy, shaped what followed.