A match loaded with meaning

On 13 May 1990, a league match between Dinamo Zagreb and Red Star Belgrade was scheduled to take place at Maksimir Stadium. On paper, it was just another fixture in the Yugoslav First League. In reality, it was a collision of politics, identity, and fear, arriving at a moment when Yugoslavia was already beginning to fracture.

The country had just held its first multi-party elections since the Second World War. In Croatia, nationalist forces had won power, while tensions between republics were rising rapidly. Football stadiums, long places of expression and release, became arenas where political feeling was no longer subtle. Maksimir was not hosting a football match. It was hosting a confrontation.

Thousands of Dinamo supporters filled the stands early, joined by a large contingent of Red Star fans who had travelled from Belgrade. These supporters were not neutral spectators. They arrived carrying symbols, chants, and anger shaped by events far beyond football.

Supporters as symbols

Dinamo’s Bad Blue Boys represented a growing Croatian nationalist identity, while Red Star’s Delije were increasingly aligned with Serbian nationalism. Their chants reflected this divide. Flags, slogans, and songs echoed political messages rather than sporting rivalry.

The presence of Arkan, a criminal figure who would later become a paramilitary leader, among the Red Star supporters added another layer of menace. His influence over sections of the Delije blurred the line between organised support and militant organisation. What unfolded inside the stadium that day would later be viewed as a warning sign of what was coming.

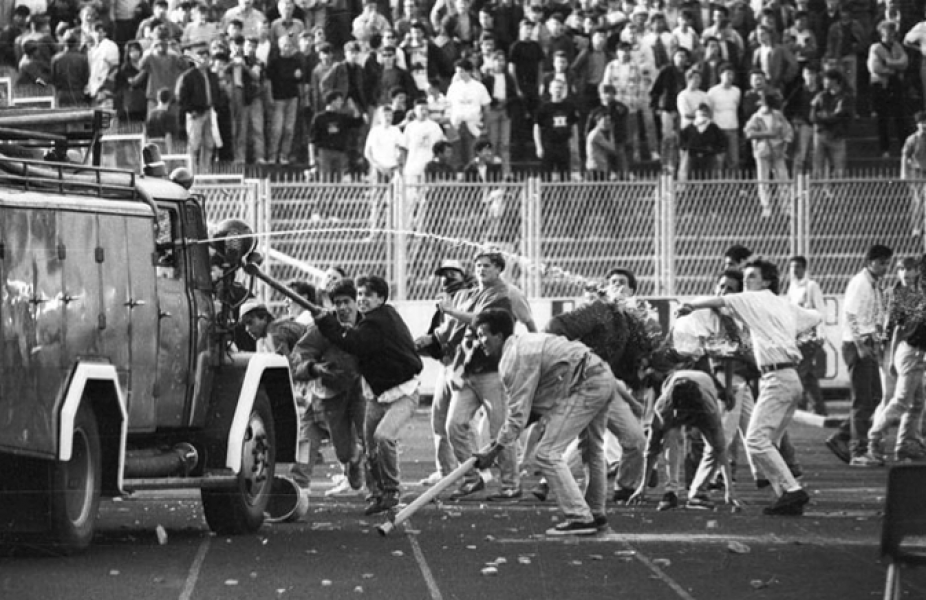

Before kick-off, violence erupted in the stands. Fights broke out, flares were thrown, and seats were ripped out. The atmosphere quickly became uncontrollable. The match never began.

Police and perception

The response of the police would become one of the most controversial aspects of the day. Many Croatian supporters believed the authorities sided with the Red Star fans, reinforcing feelings of injustice and occupation. Whether this perception was accurate or not mattered less than how it was experienced.

As clashes intensified, police moved into the stands, batons raised. Dinamo supporters spilled onto the pitch, followed by chaos from all directions. The stadium descended into scenes that resembled a battlefield more than a football ground.

For many present, this was the moment when football stopped being football. Maksimir became a physical expression of Yugoslavia’s internal collapse.

The kick that became a symbol

Amid the chaos, one image would come to define the day. Dinamo captain Zvonimir Boban ran toward a police officer who was striking a supporter and kicked him. The act was spontaneous, emotional, and instantly iconic.

Boban was suspended and punished by the football authorities, but in Croatia he became a symbol of resistance. To many, his kick represented defiance against perceived oppression. To others, it was reckless and dangerous. Regardless of interpretation, the moment transcended sport.

Years later, Boban would say he did not regret his actions. By then, the country he represented at the time no longer existed.

A league on borrowed time

The Yugoslav First League continued after Maksimir, but something fundamental had broken. Matches grew increasingly tense, supporter violence intensified, and unity became impossible to maintain. Football mirrored society, and society was moving toward conflict.

Within a year, war would engulf parts of the country. Clubs would be separated by borders rather than fixtures. Players who once shared dressing rooms would represent opposing nations. The league that had produced some of Europe’s finest footballers vanished almost overnight.

Maksimir did not cause the war. But it revealed how far Yugoslavia had already drifted.

Memory and myth

In hindsight, the Maksimir riot has taken on a mythic quality. It is often described as the moment the Yugoslav Wars began, though this simplifies a far more complex reality. The violence of the 1990s had deep political, historical, and economic roots.

Still, Maksimir remains powerful because it captured a truth. Football had become a stage where the country’s divisions were no longer hidden. The chants, the violence, and the symbols made visible what politicians were struggling to contain.

For many who witnessed it, that day felt like an ending.

Football as a warning

The riot at Maksimir stands as one of football’s most haunting moments. It shows how sport can absorb and reflect societal tension, sometimes more honestly than institutions meant to manage it. Yugoslavia’s football culture had always been intense, but at Maksimir, intensity turned into fracture.

The tragedy is not just that a match was abandoned. It is that a shared footballing world collapsed alongside a nation. The Yugoslav league, once a space of competition and creativity, became another casualty of history.

Maksimir did not predict war in detail. But it foretold that coexistence, at least in its existing form, was no longer sustainable.

In that sense, the riot was not a beginning or an end. It was a moment of clarity.