From the margins to the centre

At the start of the 1920s, South American football still occupied a peripheral position in the global imagination. Europe supplied the rules, the administrators, and the assumed authority. South America played, but was rarely consulted. By the end of the decade, that hierarchy had shifted. Uruguay and Argentina did not merely compete with Europe; they redefined what elite football could look like.

This was not achieved through gradual acceptance. It happened through confrontation, travel, and undeniable performance.

Montevideo and Buenos Aires mature

By the early 1920s, football in Montevideo and Buenos Aires had already reached a level of organisation and intensity that rivalled Europe’s strongest centres. Domestic leagues were well attended, tactically advanced, and culturally embedded.

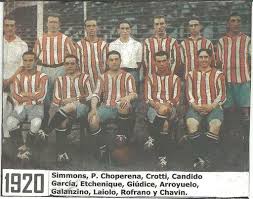

In Uruguay, the Primera División revolved around Nacional and Peñarol, clubs that had developed fierce rivalries and large followings. In Argentina, Boca Juniors, River Plate, Racing Club, and Independiente drew crowds that transformed weekends into rituals.

Players were not full-time professionals everywhere, but football was already central to urban identity. Technique, ball control, and positional understanding were valued. The game had evolved locally, not imitatively.

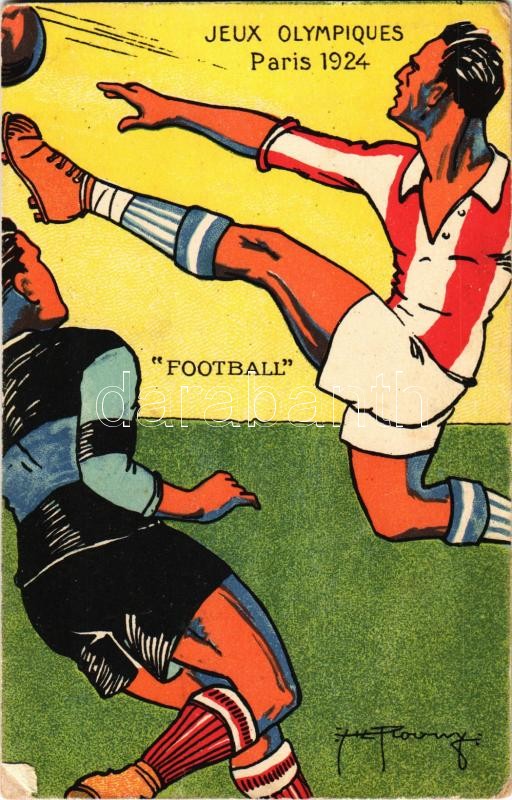

The Olympic shock of 1924

The turning point came in Paris, 1924. Uruguay arrived at the Olympic Games largely unknown to European audiences. What followed was not just victory, but revelation.

Uruguay defeated Yugoslavia, United States, France, and Switzerland with a style that surprised and unsettled observers. Short passing, off-the-ball movement, and technical calm contrasted sharply with Europe’s physical emphasis.

Players such as José Leandro Andrade, Héctor Scarone, and Pedro Petrone became instant reference points. Andrade, in particular, captivated Parisian crowds with elegance and composure. The nickname La Maravilla Negra reflected fascination as much as admiration.

Uruguay’s gold medal was not treated as an anomaly. It was understood as a statement.

Argentina’s parallel confidence

Argentina did not attend the 1924 Olympics, but its footballing confidence was already established. Domestic competitions were fiercely competitive, and Argentine clubs regularly hosted touring European sides.

In 1925, Boca Juniors embarked on a lengthy European tour, playing across Spain, Germany, and France. Their success, including victories against established opposition, reinforced the idea that South American clubs were not inferior guests, but equals.

Argentine football presented itself as expressive, intelligent, and emotionally charged. Matches were theatrical. Players were adored. The game was lived rather than observed.

Tours as cultural exchange

Tours became South America’s primary outward-facing tool. European clubs travelled to Buenos Aires and Montevideo, often expecting exhibition matches and discovering competition instead.

When Real Madrid toured South America in the late 1920s, they encountered intense crowds and technical opponents who matched them in every department. These encounters were reported extensively in European newspapers, altering perceptions.

Tours worked both ways. South American players adapted quickly to foreign pitches and refereeing styles. The idea that their football was parochial or naïve collapsed under scrutiny.

The second confirmation in 1928

If Paris had introduced Uruguay, Amsterdam 1928 confirmed them. Uruguay again won Olympic gold, defeating Argentina in a dramatic final replay after an initial draw.

The final was watched closely across Europe. It was no longer exotic. It was elite football. The rivalry between Uruguay and Argentina, already intense in the Copa América, now carried global significance.

The message was clear: South America was not borrowing football culture. It was producing it.

National identity through football

For Uruguay, football became inseparable from national identity. A small country asserting itself internationally, Uruguay used football as cultural diplomacy. Victories mattered beyond sport.

Argentina’s relationship was more complex. Football expressed urban modernity, immigration, and class tension. Buenos Aires saw the game as both popular art and competitive struggle.

In both countries, football was no longer imitation of Europe. It was assertion.

The stylistic shift

European observers struggled to categorise what they saw. South American teams emphasised close control, patience, and improvisation. Physicality existed, but was secondary to intelligence.

This challenged assumptions about progress. Europe had believed itself tactically superior. The 1920s exposed that belief as incomplete.

Coaches, journalists, and players began studying South American methods. Influence flowed in both directions.

Towards global football

By the end of the decade, the centre of gravity had shifted. Football was no longer anchored solely in Britain or Central Europe. It had become genuinely transcontinental.

This shift paved the way for the 1930 World Cup, hosted by Uruguay. The decision reflected recognition, not generosity. South America had earned central status.

The 1920s did not globalise football completely. But they ended European exclusivity.

What the decade changed

Uruguay and Argentina did not just win matches. They changed perception. They forced football to acknowledge that excellence could emerge independently, shaped by different cultures and values.

The outward movement of South American football in the 1920s was not expansion. It was arrival.