From experiment to expectation

By the early 1920s, league football already existed in many countries, but permanence did not. Competitions started and stopped, formats shifted yearly, and clubs entered without certainty that the structure around them would survive. What the decade changed was not the idea of leagues, but their reliability.

The 1920s were the moment when league systems stopped feeling provisional and began to feel inevitable.

England’s expansion and consolidation

England entered the decade with the oldest league system, yet even there stability was not guaranteed. The Football League expanded dramatically after the First World War, creating the Third Division in 1920 and splitting it into North and South sections a year later.

This expansion mattered because it formalised hierarchy. Clubs such as Plymouth Argyle, Port Vale, and Southampton were no longer navigating ad hoc regional arrangements. They now belonged to a fixed national pyramid with promotion, relegation, and predictable schedules.

Not all survived the pressure. Aberdare Athletic and Durham City fell out of the League by the mid-1920s. But the structure itself did not collapse. Instead, it absorbed failure and continued.

That resilience was new.

Central Europe builds systems, not just teams

In Austria, football’s transformation was sharper. Vienna had long hosted competitive leagues, but professionalism arrived officially in 1924, forcing the game to choose between permanence and chaos.

The Wiener Liga became one of Europe’s first fully professional leagues. Clubs like Rapid Wien, Austria Wien, and First Vienna FC adapted quickly, investing in administration as much as players. Others disappeared.

The key change was expectation. Seasons were planned years ahead. Fixtures became obligations rather than aspirations. The league was no longer an experiment in progress.

Hungary followed a similar path. The Hungarian League stabilised around clubs such as MTK Budapest and Ferencváros, with regularised seasons and consistent governance. The dominance of Budapest clubs was unequal, but it was stable.

Stability did not mean fairness. It meant continuity.

Italy reorganises before modernity

Italian football in the early 1920s was fragmented, with regional competitions feeding into national finals. The decade forced reform.

Through a series of restructurings, Italy moved toward a unified national league, culminating in the creation of Serie A in 1929. Clubs like Juventus, Internazionale, and Genoa benefited from clearer pathways and regular elite competition.

The process was turbulent. Smaller provincial clubs struggled with travel and finance. But the direction was unmistakable. League football in Italy was no longer seasonal improvisation. It was institutional design.

The 1920s made national competition permanent even before it became modern.

Germany’s regional permanence

Germany did not create a national league in the 1920s, but it achieved something equally important: durable regional systems.

The Bezirksligen, later evolving into Oberligen, provided consistent, repeatable competition across regions such as Bavaria, Westphalia, and Saxony. Clubs like 1. FC Nürnberg and SpVgg Fürth thrived within these structures, knowing the framework would persist.

This mattered because it allowed long-term planning. Youth development, stadium investment, and supporter culture all depended on continuity.

Germany proved that stability did not require centralisation. It required reliability.

France’s delayed but necessary order

France lagged behind structurally, remaining officially amateur throughout the 1920s. Yet even here, the decade laid groundwork.

Regional leagues under the FFF became more consistent, with clearer qualification routes to national competitions like the Coupe de France, founded in 1917 but gaining real prominence during the 1920s.

Clubs such as CA Paris, Red Star, and FC Sète operated within increasingly predictable frameworks. When professionalism arrived in the 1930s, it did so onto foundations built a decade earlier.

The 1920s taught French football how to organise, even if it delayed how to pay.

South America formalises intensity

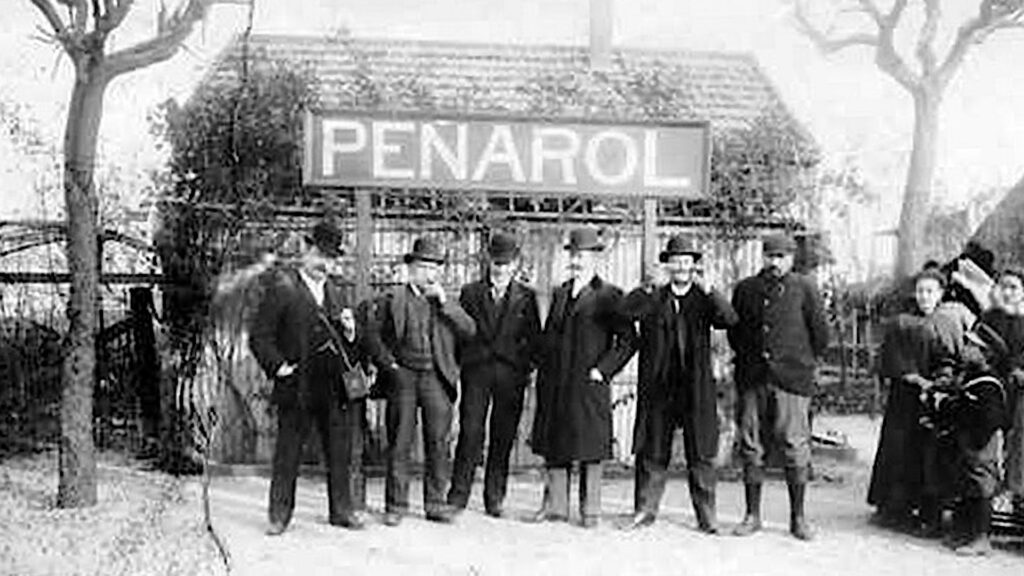

In Uruguay and Argentina, league football already attracted mass crowds, but the 1920s brought administrative maturity.

The Uruguayan Primera División stabilised around Montevideo’s giants Nacional and Peñarol, creating seasons that mattered culturally and economically. League titles became historical markers rather than fleeting honours.

In Argentina, the Primera División grew in stature despite disputes over amateurism and professionalism. Even during splits later in the decade, the idea of a permanent league calendar remained unquestioned.

Instability existed, but it existed within systems that expected to endure.

Why permanence began here

Earlier decades had leagues, but they lacked insulation. A war, a dispute, or a financial crisis could erase them entirely. The 1920s introduced mechanisms that absorbed shock.

Promotion and relegation normalised failure. Governing bodies gained authority. Calendars standardised. Clubs began to exist within structures larger than themselves.

Crucially, supporters adjusted expectations. Football was no longer an occasional event. It was a season, then another, then another.

Habit created permanence as much as administration did.

Who benefitted, who disappeared

Stable league systems favoured clubs with resources, urban bases, and organisational competence. Rural teams, works clubs, and poorly administered sides were squeezed out.

This imbalance is often criticised retrospectively, but it was part of stabilisation. Systems became selective because they had to be.

Survival became a competitive skill.

The long shadow of the 1920s

By the end of the decade, football leagues across Europe and South America shared a new characteristic: expectation of continuation. Even where formats changed, disappearance was no longer normal.

This is why permanence began in the 1920s, not later. The 1930s refined structures. The post-war era commercialised them. But the psychological shift happened earlier.

Football learned how to last.