Fame before broadcasting

Football celebrity did not begin with television, sponsorships, or global marketing. It began in the 1920s, shaped by newspapers, railway timetables, and crowds large enough to turn players into public figures. Long before faces were transmitted into homes, footballers became recognisable through repetition: names in print, performances witnessed in person, and reputations carried between cities.

The 1920s created the conditions for fame without modern media. It was a decade where footballers became known not just locally, but nationally and, in some cases, internationally.

Newspapers and the printed hero

The most powerful force behind early football celebrity was the press. Daily and weekly newspapers expanded sports coverage dramatically after the First World War. Match reports grew longer, player names appeared more frequently, and individual performances were dissected with unusual attention.

In England, papers like the Daily Express and Athletic News began to single out players as personalities. Billy Meredith, already famous before the war, remained a household name well into the 1920s through column inches rather than appearances. His image, moustache, and reputation survived even as his playing days faded.

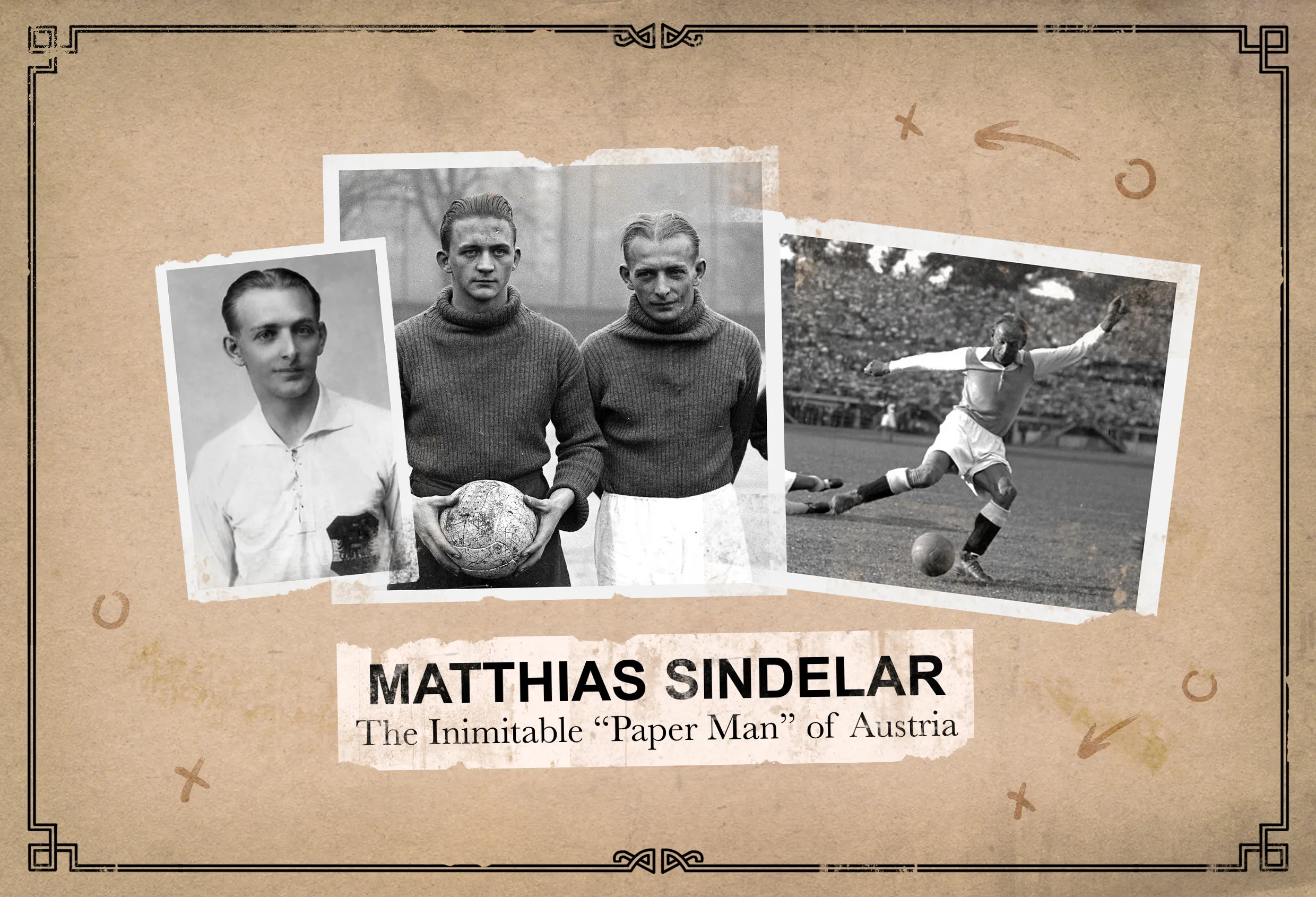

On the continent, the effect was sharper. In Vienna, sports newspapers elevated players such as Matthias Sindelar into cultural figures. Sindelar’s name appeared as often in café conversation as it did in match reports, and his style of play was described in literary terms rather than technical ones.

The press did not just report football. It framed characters.

Railways and repeat visibility

Celebrity depends on being seen, and the railway made that possible. The 1920s were the first decade in which regular inter-city travel allowed players to appear before the same audiences multiple times a season.

League systems expanded geographically. National cups required travel. Friendly tours became common. A player who performed well away from home could quickly build recognition beyond his local base.

In Italy, Virginio Rosetta became one of the first truly national football figures through his appearances for Pro Vercelli and later Juventus, travelling regularly across the country during a period when Italy was still regionally fragmented. His name became familiar not because of broadcasts, but because he kept arriving.

Railways turned footballers into recurring figures rather than fleeting visitors.

Crowds large enough to create myth

The scale of crowds mattered. Stadium attendances in the 1920s reached levels that created shared memory. Tens of thousands watched the same actions simultaneously, then carried those moments back to workplaces, cafés, and homes.

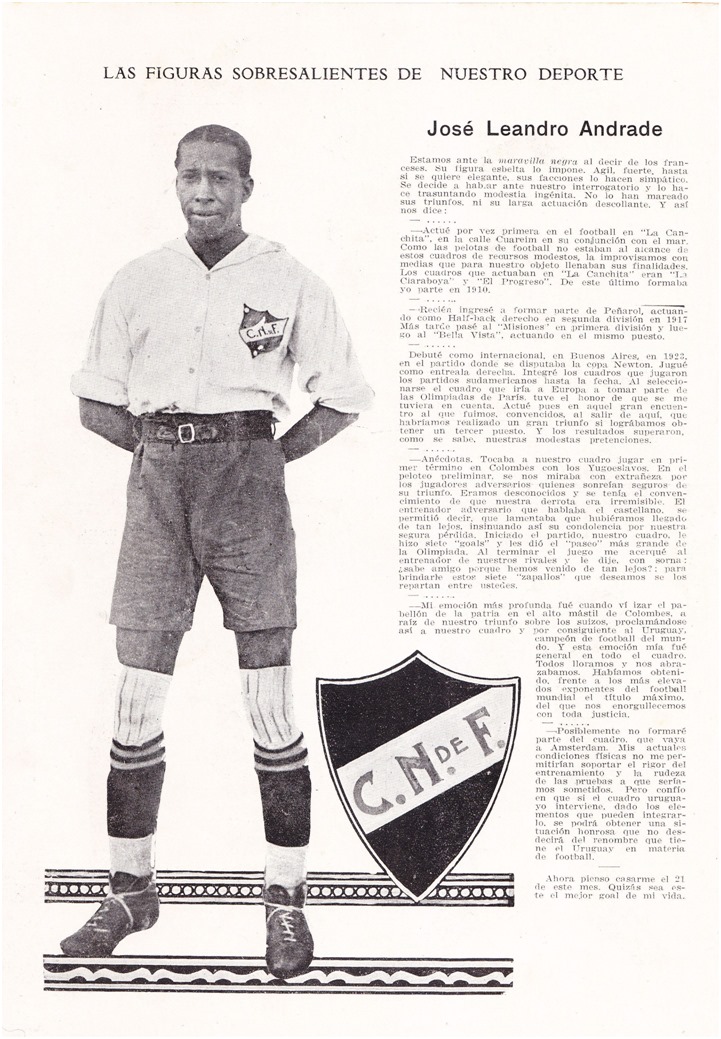

In Uruguay, José Leandro Andrade became famous through presence alone. His performances at the 1924 Paris Olympics were witnessed live by European crowds unfamiliar with South American football. Andrade’s elegance, movement, and composure stood out immediately.

Though few could watch him regularly, those who did remembered him vividly. His reputation spread through eyewitness accounts rather than footage. In this way, celebrity functioned as oral history amplified by print.

Tours and international exposure

Football tours were essential to early fame. Clubs and national teams travelled for weeks or months, playing exhibitions that blurred competition and spectacle.

Boca Juniors’ 1925 European tour transformed players such as Cesáreo Onzari into international figures. Onzari’s goal directly from a corner kick against Uruguay, later known as an olímpico, was reported widely in European papers even though it occurred thousands of kilometres away.

Similarly, Central European touring sides introduced players repeatedly to foreign audiences. Hungarian and Austrian teams played in Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, carrying reputations ahead of them.

A footballer could become famous in cities he had never lived in.

The role of national teams

International football accelerated recognition. The Olympics, especially the tournaments of 1924 in Paris and 1928 in Amsterdam, created concentrated moments of exposure.

Uruguay’s victories made players like Andrade and Héctor Scarone instantly recognisable beyond South America. Their fame was not tied to club loyalty but to national representation, which carried symbolic weight in the interwar period.

In Central Europe, international matches between Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia were major cultural events. Players became embodiments of style and identity. Sindelar was not just admired; he was interpreted as Austrian football.

Celebrity merged with national self-image.

Fashion, posture, and recognisability

Early football celebrities were recognisable not only by name, but by appearance and movement. Without television, distinctive traits mattered.

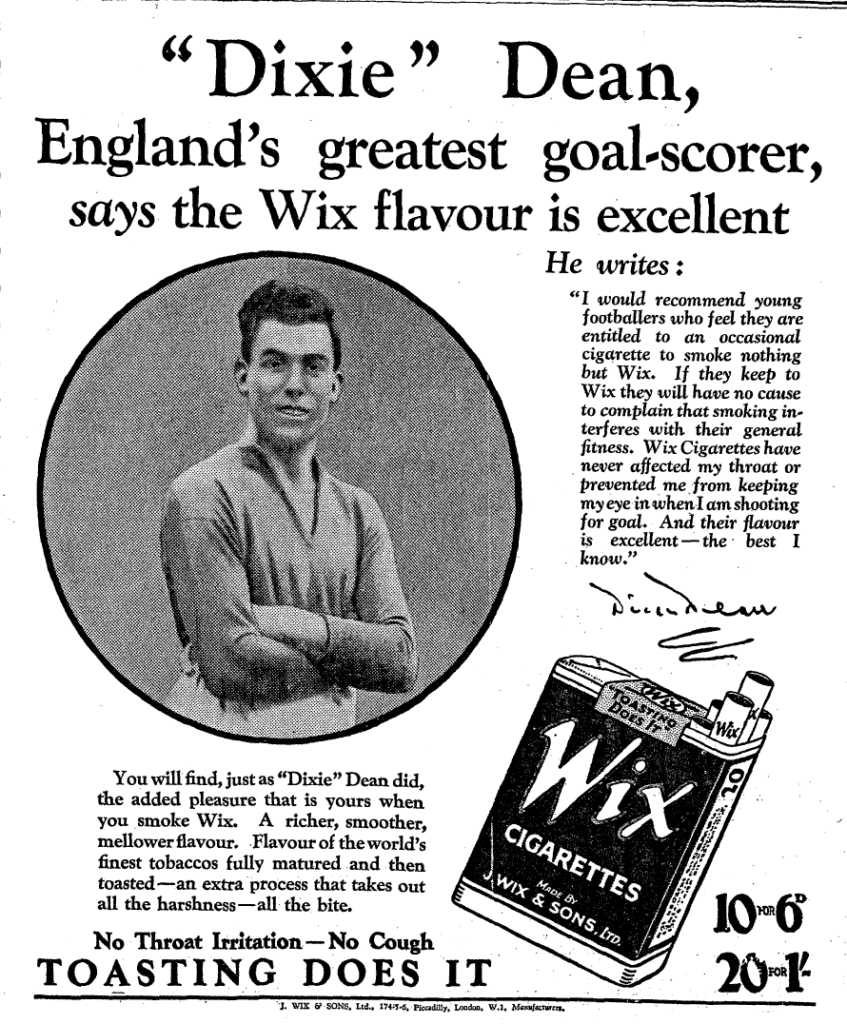

Sindelar’s light frame and upright posture were described repeatedly in print. Andrade’s elegance and dancing footwork were emphasised in contrast to European physicality. In England, Dixie Dean became identifiable through his power and relentlessness rather than finesse.

These descriptions mattered. They allowed readers who had never seen the players to imagine them clearly. Style became a form of branding long before the term existed.

Limits of early fame

Despite growing recognition, football celebrity in the 1920s remained fragile. Players were still workers. Most lived modestly, travelled second class, and returned to anonymity quickly after retirement.

There were no endorsement deals, no personal brands, and little financial security. Fame existed almost entirely within football spaces. Outside them, players often went unnoticed.

This limitation shaped behaviour. Celebrities were accessible. They drank in the same cafés, walked the same streets, and travelled on the same trains as supporters.

Celebrity had proximity.

Why the 1920s mattered

The decade did not create global stars in the modern sense. It created recognisable figures — players known by name, style, and reputation across regions.

The mechanisms were simple: print, travel, and crowds. Together, they turned footballers into repeat presences rather than local curiosities.

Later technologies would magnify this process, but the template was already in place. Football learned how to make individuals visible within a collective sport.

What remained

By the end of the 1920s, footballers could be famous without being wealthy, known without being distant, admired without being untouchable. Their celebrity was rooted in performance witnessed and described, not consumed through screens.

The first football celebrities were not products of media empires. They were created by trains arriving on time, newspapers printed overnight, and crowds large enough to remember.

That combination changed the game forever.